The classics are done and dusted and it is now time to focus on the grand tours. The first of those starts in just a few days time when the cycling-mad country of Italy invites the world to a two-wheeled festival of versatile racing with steep mountains, uncontrollable terrain, long time trials and fast bunch kicks. This year's Italian grand tour contains a bit of it all as a well-balanced route gradually builds up to its crescendo in the final week of racing. CyclingQuotes.com takes a look at each of the 21 stages that will make for a huge three-week celebration of cycling.

When Michele Acquarone took over the reins from Angelo Zomegnan as race director of the Giro d'Italia, he had a firm objective. He wanted to internationalize what was by many seen as a mostly Italian race in an attempt to challenge the position of the Tour de France as the world's leading bike race, and the first premise for success in that regard was the attraction of more international stars to the race's line-up.

To achieve this Acquarone knew that he had to listen more to the riders' wishes. The final two routes designed by Zomegnan had been heavily criticized as being way too hard and even inhuman as the number of mountain stages and excessively steep climbs just continued to grow. The nature of the course convinced many stars to skip the Italian race in favour of the two remaining grand tours.

When Acquarone revealed the route for the 2012 edition, it represented a clear dissociation with the legacy of Zomegnan. Gone were the excessively steep climbs, the uncountable number of mountain finishes and long transfers and instead the race was built much more upon the riders' wishes. The race still had its spectacular highlights - most prominently a final mountain stage to the top of the Stelvio climb designed by the fans - but the anatomy of the race was much more human.

With the design of the 2013 course, Acquarone continued along the same path with another balanced course and even though he is no longer in charge of the Italian grand tour, his legacy was evident when the 2014 route was presented. The 2015 follows the same pattern. This year's race offers plenty of mountain stages and a number of other hard stages in the difficult Italian terrain. Once again the race has been built up to reach its crescendo with a festival of mountain stages in the final week but the distances have been limited, the transfers have been reduced and the riders get a much more gentle introduction to the race.

For several years, the race has been known as a very mountainous affair that is mainly decided by the climbing. However, the race has usually also included three time trials: a team time trial, a mountain time trial and a more traditional individual TT. With Italians struggling in the time trials, there has been a tendency to favour climbers over time triallists and the latter TT has usually been a rather short one. With the desire to attract more international stars, however, the 2013 edition was the first since 2009 to include a really long race against the clock and last year the trend continued. A long 41.9km race against the clock gave the all-rounders much better prospects in their battle against the climbers. The change has been a successful one as the inclusion of the time trial in 2013 was one of the main reasons for Bradley Wiggins’ participation and last year Richie Porte was tempted by the prospect until illness took him out of the race.

This year the organizers have taken one step further in that direction and there is no doubt that this is the course least suited to climbers since 2009 when Denis Menchov laid the foundations for an overall victory by winning a mammoth time trial of more than 60km. This year the number of TTs may have been reduced to three but it is the mountain time trial that has been skipped. Furthermore, the flat time trial will be held over a massive 59.4km and even though it includes a rolling second half, the first part is completely flat and will make the climbers suffer.

To make their woes even worse, the climbing will be a lot easier than it has usually been. The number of summit finishes has been reduced from 9 to 6 – and an uphill finish on a short, steep ramp – but that would not be a major issue if the finishing climbs had been steep and tough. However, none of the summit finishes include very hard final ascents and on paper they will not be able to create big time differences. There are still lots of very hard, steep climbs like the Passo Daone, Colle delle Finestre and Mortirolo, but they all come as the penultimate challenge, preceding a much easier final climb. Alberto Contador has already regretted this characteristic of the race and on paper the single most decisive stage will be the long time trial.

While the climbers will regret the design of the course, the punchy Ardennes specialists lick their lips in anticipation. The first two weeks of the race are littered with hilly stages that look like small Ardennes classics and for those riders, the main challenge may be to decide which stages to really target. It is no wonder that Philippe Gilbert has chosen this year’s race as his best chance to take the maglia rosa and that Simon Gerrans made a late decision to include the race on his schedule after an injury-plagued first part of the season.

After Alessandro Petacchi’s heydays when he managed to win as many as 9 stages in a single edition, the Giro d’Italia has had limited opportunities for the sprinters. Last year the start in Ireland meant that the first week was unusually sprint-friendly but this year the race is back to a traditional format. The pure sprinters will only have 6 chances to shine and they are spread out equally throughout the race, with two opportunities in the first two weeks. In fact, the first week will be unusually tough for the fast finishers as they will have to wait three days before they get another chance after the first bunch sprint. As opposed to this, there are lots of opportunities for the Michael Matthews kind of sprinters. For the second year in a row, however, the points classification is favouring sprinters and as the final stage will again be one for them, they have plenty of incentive to get to the finish that will return to Milan after a two-year absence.

The GC riders will be pleased not to have last year’s nervous start in windy and rainy Ireland but they still have to get through almost two weeks of survival before the major stages are scheduled. The first week is a parade of small classics with only two summit finishes that are pretty easy. The first half of the second week is again for stage hunters and we will get to the third weekend before it is finally time for the GC riders to kick into action. The crucial time trial comes in stage 14 and one day later it is time for the first summit finish in the high mountains.

The main challenges come in the third week where the riders will have to tackle no less than four mountain stages, with stages 16, 19 and 20 set to be the toughest and most spectacular. That is certainly a cause for concern for Alberto Contador who would have preferred to hit the cruise control button in the final week to save energy for the Tour de France. Now he is likely to find himself with time to make up on Richie Porte and he will have to be close to his best to get rid of the Australian in a final week that has lots of climbs but no very tough summit finish.

All things considered, the internationalization strategy seems to be a huge success as international stars like Alberto Contador, Richie, Porte, Rigoberto Uran, Jurgen Van Den Broeck, Steven Kruijswijk, Leopold König, Przemylaw Niemiec, Carlos BetancurRyder Hesjedal take on big Italian stage race riders like Fabio Aru, Domenico Pozzovivo, Damiano Caruso, Davide Formolo and Franco Pellizottiin a race that has all the potential to be another fantastic celebration of the sport of cycling.

Below we give an analysis of each of the race's 21 stages. RCS have rated the difficulty of each stage by assigning between 1 and 5 stars and that assessment is indicated in the description.

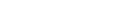

Stage 1, Saturday May 9: San Lorenzo al Mare – Sanremo, 17.6km TTT (***)

After the spectacular start in Belfast, the Grande Partenza is back on Italian soil for the 2015 edition of the first grand tour. However, the opening stage is very similar to the one that kicked off the show in Northern Ireland one year ago. While the Tour de France has mostly started with a prologue, the Giro d’Italia and Vuelta a Espana have often preferred to kick off their event with the discipline that is widely regarded as the most beautiful in cycling.

A team time trial is the perfect way to present the squads, their rosters and their ambitions and for the second year in a row, it will be the collective discipline that starts the event. RCS have had team time trials on the opening stage for most of the past decade, with the 2012 and 2013 being the recent exceptions. They have mostly been flat affair suited to specialists and have always been kept at a pretty short distance which means that the time differences are usually limited.

This year’s course is 17.6km long, starts in a spectacular setting on the Ligurian coast in the city of San Lorenzo al Mare and finishes in one of the most iconic cycling cities, Sanremo. This TTT stage is raced almost entirely along the “Cycling Riviera” cycle path that features, on average, a narrow roadway (this was the former railway, hard-surfaced and re-arranged) and a few well-lighted tunnels along the course. Half-distance, in Arma di Taggia, two sharp turns and an underpass lead out of the cycle path, on to the split-time recording point at the 9.9km mark, and then back to the cycle path, up to the home straight on Lungomare Italo Calvino (where the finish line of Milano-Sanremo was set from 2008 to 2014). The stage profile features no challenging points and is completely flat.

The last kilometres run entirely across the city, and mostly along the “Cycling Riviera” cycle path. The route leaves the bike lane with a double turn approx. 500 m from the finish line, up to the final right-hand half-bend leading to the 250-m long home straight, on 7-m wide asphalt road.

If the weather allows it, the opening team time trial will provide some spectacular images of the coastline but for the riders it will be 20 minutes of pure suffering. Time differences in short team time trials are always very small and the seconds gained in this event are unlikely to be decisive at the end of three weeks of hard racing. However, it will be very important to get the race off to a good start from a psychological point of view before the GC riders head into a few days that are mostly about survival. The course is completely flat and unlike last year, there are no technical challenges. This is a stage for the specialists and the teams that really focus on this discipline and it would be no surprise to see Orica-GreenEDGE repeat last year’s victory. Almost half of their roster is selected almost solely because of this stage which is a very big goal. Fabio Aru and Domenico Pozzovivo both hope to limit their losses to Alberto Contador, Richie Porte and Rigoberto Uran who all have strong teams for this stage while riders like Philippe Gilbert, Michael Matthews and Simon Gerrans hope to remain within striking distance of the maglia rosa.

Sanremo doesn’t often feature on the Giro d’Italia course but hast hosted a stage finish 11 times in the past, most recently in 2001 when the riders tackled a difficult stage in its hilly hinterland in 2001. Pietro Caucchioli beat Jose Azevedo in a 2-rider sprint while Jan Ullrich took third 27 seconds later. Last year’s team time trial was won by Orica-GreenEDGE who put Svein Tuft in the maglia rosa on his birthday. In 2011, HTC-Highroad took the win on the opening day in Torino to give Marco Pinotti a stint in pink and they were also the fastest in 2009 when Mark Cavendish took the early lead. In 2008, Garmin-Chipotle won the opener while Liquigas set Danilo Di Luca up for the overall victory by winning the 2007 opener.

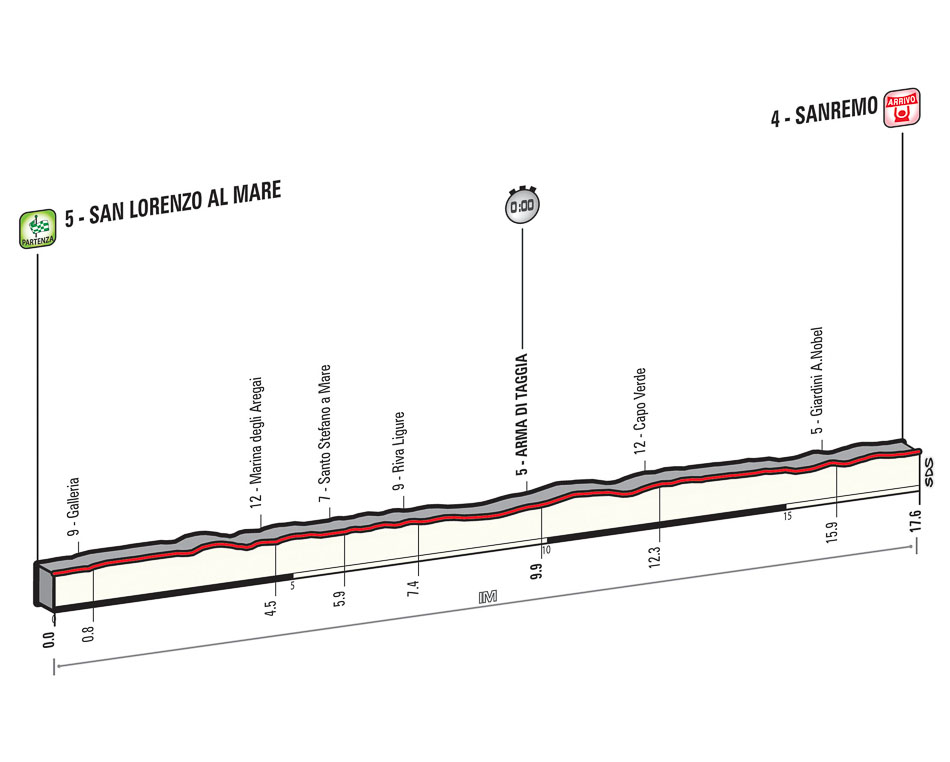

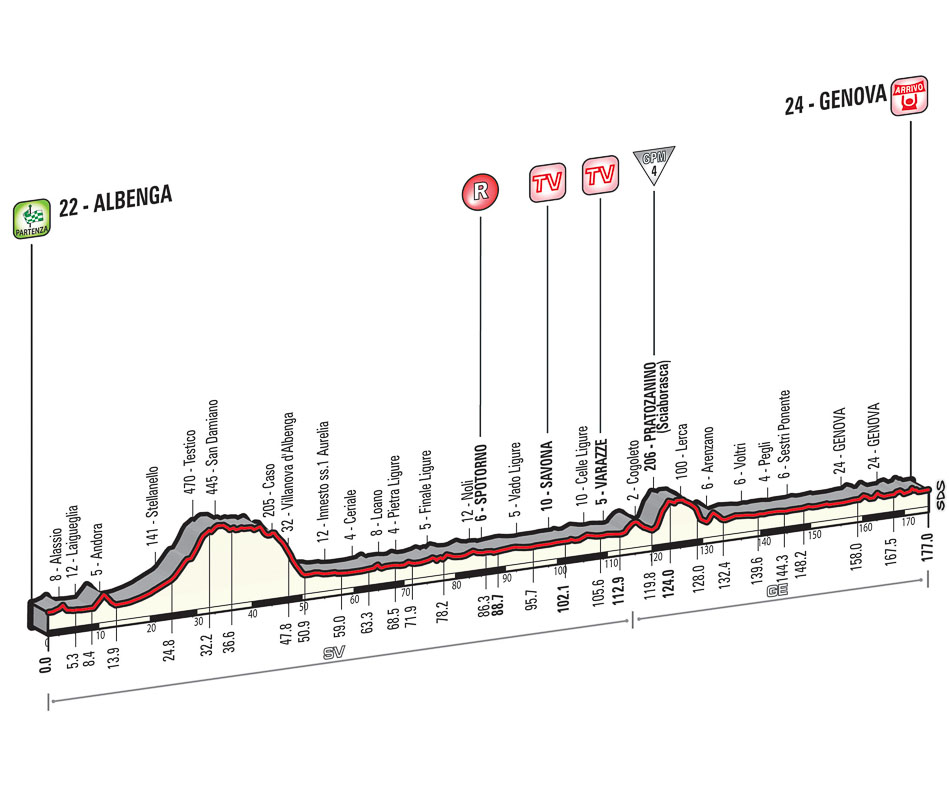

Stage 2, Sunday May 10: Albenga – Genova, 177.0km (**)

Unlike the Tour de France, the Giro d’Italia mostly includes hilly stages very early in the race but they have mostly reserved the first road stage for the sprinters. That won’t be any differing in 2015 as the second stage is a mostly flat affair along the coast. The fast finishers have to be ready from the start as they will have to wait a few more days before getting their next opportunity and it will be very different from last year where the flat Irish roads made the first days a sprint festival.

The 177.0km stage starts in Albenga and ends in the biggest city on the Ligurian coast, Genoca. This first mass-start stage has a mainly flat route, but features a wavier and more challenging profile in the first part, with the Testico climb (known from the Trofeo Laigueglia) just 32 kilometres from the start as the riders do a small loop in the hilly hinterland, followed by constant gentle undulations, and the “Capi” on the Aurelia road, along the coast of the Western Riviera. The Pratozanino ascent (4th cat., 4.2km, 4.9%, max. 10%), just past Cogoleto, will be the first categorised climb of the 2015 Giro but its summit is located with 53km to go. After reaching Genova, the route takes the 9.5-km city circuit, to be covered twice.

The 9.5-km final circuit, running entirely along city roads, will be covered twice. The finish line is set in Via XX Settembre. The stage course runs through Piazza de Ferrari (with a short stretch on stone-slab paving), then goes down to Piazza Brignole, where the road slowly starts to rise, up to Piazza Verdi. Here, a 1-km dash with a 4% gradient leads to Albaro, followed by a false-flat drag and the descent down into Boccadasse, where the route reaches the seafront. The course runs flat up to the last kilometre (completely straight), where the road climbs steadily, with gradients of around 2%. The home straight is on 8-m wide asphalt road and comes after the riders have left the coast just after the 2km to go mark where they take a right-hand turn that is followed by a left-hand turn just after the flamme rouge

The course features two tough climbs along the way but as the final 50km are almost completely flat, it is very hard to imagine that this won’t be a day for the sprinters. Most of the stage takes place along the coast but the wind rarely plays a role in this part of the country. This should make the race less nervous but it is always a tense affair in the first road stage of a grand tour. That will be very evident on the finishing circuit which is very technical in the first part. For the sprinters, it will be important to be in a good position and the short climb in the early part may take the sting out of the legs of some of them. With a long finishing straight, however, the scene is set for a big battle between the fast finishers on the slightly ascending road in Genova.

Genova has hosted a Giro stage finish 41 times, most recently in 2004 when Bradley McGee beat Olaf Pollack in the opening prologue. In 2000, Alvaro Gonzalez de Galdeano successfully completed a solo breakaway by holding off Jan Svorada and the rest of the peloton by 24 seconds.

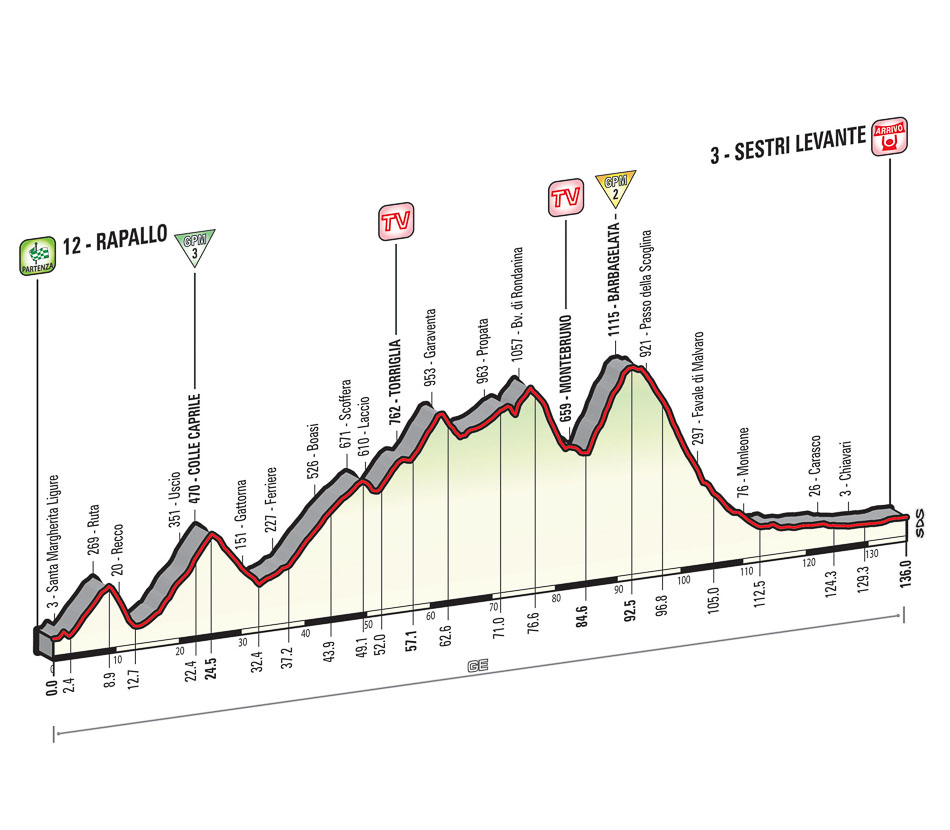

Stage 3, Monday May 11: Rapallo – Sestri Levante, 136km (***)

Due to the Italian geography, the Giro d’Italia organizers have the chance to include hilly stages at almost any point in the race and this means that the riders usually head into the hills pretty early in the race. This will again be the case in 2015 when the riders will tackle the first serious climbing already on the third day. With a long downhill run to the finish, however, it won’t be a day for the GC riders and instead the classics riders and strong sprinters will have their eyes firmly focused on this one.

At just 136km, it is a very short affair that brings the riders from Rapallo on the Ligurian coast – where the tragic stage that cost Wouter Weylandt his life, ended – to Sestri Levante just a few kilometres further down the coast. The riders build the distance by doing a big loop in the hilly hinterland before they descend to the coast where they will follow the flat coastal road to the finish.

This stage has a mostly challenging and rough course (with a total difference in altitude of nearly 2,300 m over 136 km), with the exception of the last 10 km. The first 110 kilometres (out of 136) feature a never-ending series of curves switching in both directions, undulations, climbs and descents on narrow mountain roads. The route first takes in the Ruta di Camogli climb, just a few kilometres after the start, followed by Colle Caprile (category 3, 11.8km, 3.8%, max. 9%). The course then clears the Scoffera climb, runs across Torriglia and skirts around Lago del Brugneto. It plummets down into Montebruno, with some technical sections, then climbs up again to the Barbagelata KOM summit (category 2, 5.7km, 8.1%, max. 12%) whose summit is located with 43.5km to go, followed by a very long descent (with a technical first half, up to Passo della Scoglina) leading to Chiavari and, eventually, to the finish after a flat final 6.7km section along the coast. The final climb is steepest at the bottom and has an easier section near the top before it again includes a steep 9.8% section of 500m in the final part.

The final 7 kilometres of the stage course roll along via Aurelia. The route is mainly flat, with the classic undulations of coastal roads. Two kilometres before the finish, a tunnel protecting against rockfall (almost entirely open, with “windows” along the side facing the sea) leads to a short descent, which ends some 1,200 m before the finish. With 850 m to go, a roundabout causes a slight offset in the route. The home straight is 850-m long, on 6.5-m wide asphalt road and very slightly descending.

This stage has a huge amount of climbing and is definitely not a day for the pure sprinters. Instead, it is an obvious target for riders like Michael Matthews, Simon Gerrans and Philippe Gilbert who both have their eyes on a stage win and the maglia rosa while local riders like Enrico Battaglin, Sonny Colbrelli, Francesco Gavazzi and Oscar Gatto will also have red-circled this day as their first chance. Orica-GreenEDGE and BMC will probably control the stage firmly and it will be hard for anyone to successfully complete a breakaway. However, short hilly stages can be difficult to control and a strong group that takes off early or late in the stage may cause a surprise but the most likely outcome is a sprint from a reduced group.

Sestri Levante hosted a stage finish four times, most recently in 2012 when Lars Bak attacked solo from a breakaway to take his first grand tour stage win. In 2006, it was also a break that decided the stage, with Joan Horrach launching a late attack out of a lead group to take the win with a 5-second margin.

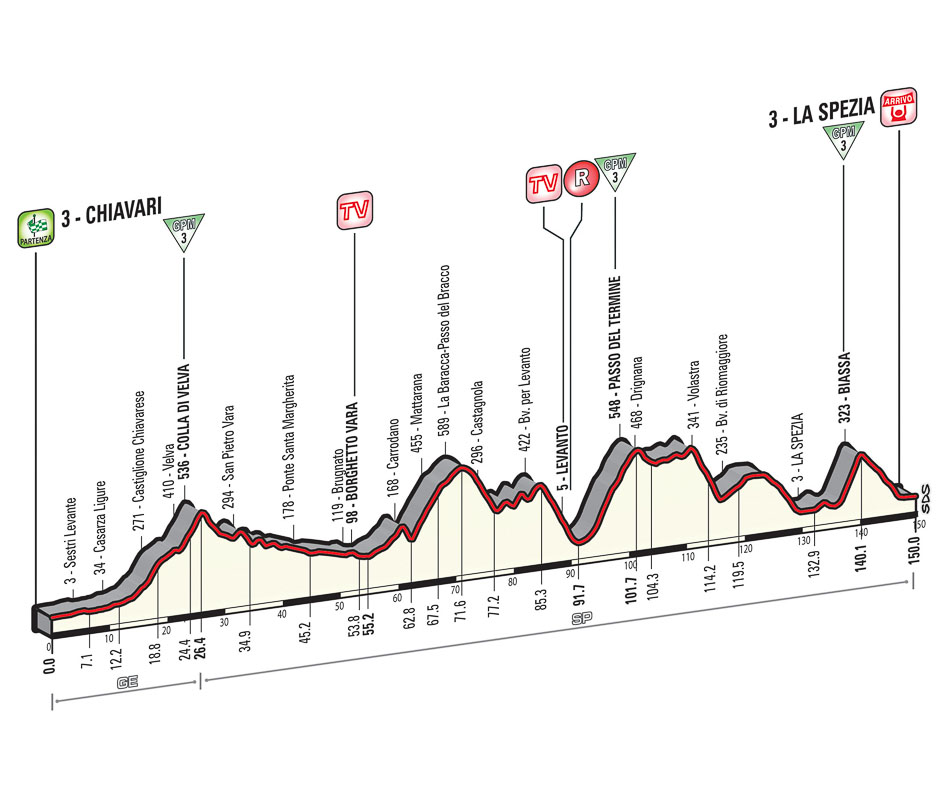

Stage 4, Tuesday May 12: Chiavari – La Spezia, 150km (****)

It is no surprise that Philippe Gilbert had a look at the Giro course and decided that 2015 was the year to try to take the maglia rosa and that Simon Gerrans made a late decision to include the Italian grand tour on his schedule. The first part of the race is loaded with opportunities for Ardennes specialists and after stage 2 which was maybe slightly better suited to the Michael Matthews kind of sprinters, stage 4 is one for the punchy classics sprinters.

Like the previous stage, it is a very short affair as it brings the riders over juts 150km from Chiavari to La Spezia as the riders continue their journey down the Ligurian coast. Again they will head into the hilly hinterland to include a significant amount of climbing.

This stage is short (150 km), but very technical and intricate. It features an unceasing series of climbs, descents and winding roads among the mountains, on mainly narrow roads. After the first few kilometres on level terrain, the route takes in the Colla di Velva ascent (category 3, 14.2km, 3.5%, max. 9%), enters Val di Vara and tackles the Passo del Bracco climb. A few technical stretches then lead to the Cinque Terre. The route rolls past Levanto, and then climbs up Passo del Termine (category 3, 8.8km, 6.1%, max. 10%). After an easy start, the climb includes two sections of around 8% that are split by an easier 4.5% kilometre at the midpoint. It levels out near the top. After Riomaggiore – where Denis Menchov won the long time trial in 2009 – the “Biassa” tunnel (over 1 km in length) leads to the Gulf of La Spezia. Here, after passing the finish line, the route takes a lap on a 17.1-km circuit.

The final circuit, rolling partly on city roads, is very challenging and intricate. The first part (around 4 km) runs through the urban area, and is marked by straight roads and 90-degree turns (with a slight uphill sector on cobbles, stretching about 1 km in length). The following Biassa ascent (category 3, 3.4km, 4.7%, max. 14%) rises with a 5% gradient over 3.5 km, and with ramps always exceeding 10% over the last kilometre, with peaks topping out at 14%. A long, panoramic, pretty technical descent begins 10 km before the finish, and ends with 3 km to go. The final 3 kilometres run on long, straight and level roads. The home straight is 700-m long on 8-m wide asphalt road. There are 90-degree runs with 2.5km, 1.8km and 700m to go.

This is another stage that has been highlighted by the classics riders who both hope for a stage victory and a stint in the maglia rosa. Short, hilly stages are always difficult to control but with BMC and Orica-GreenEDGE fully ready to support their captains, it will be hard for anyone to make a long-distance break stick this early in a grand tour. Hence, it will probably all come down to a battle on the final climb where the difference can be made in the steep top section. The GC riders will have to stay attentive to avoid any time loss while the classics riders will go on the attack. With a technical descent, there is a chance that a splits can occur and that a small group can make it to the finish, especially if it’s a wet day. However, the most likely outcome is again a sprint from a group which will probably be a lot smaller than the one that decided the third stage.

La Spezia has hosted a stage finis 6 times in the past, most recently in 1989 when Laurent Fignon won the stage. It is famously known as Alessandro Petacchi’s home city. The veteran would love to win on home roads in his final grand tour but is unlikely to play a role on a course that is too hard for him.

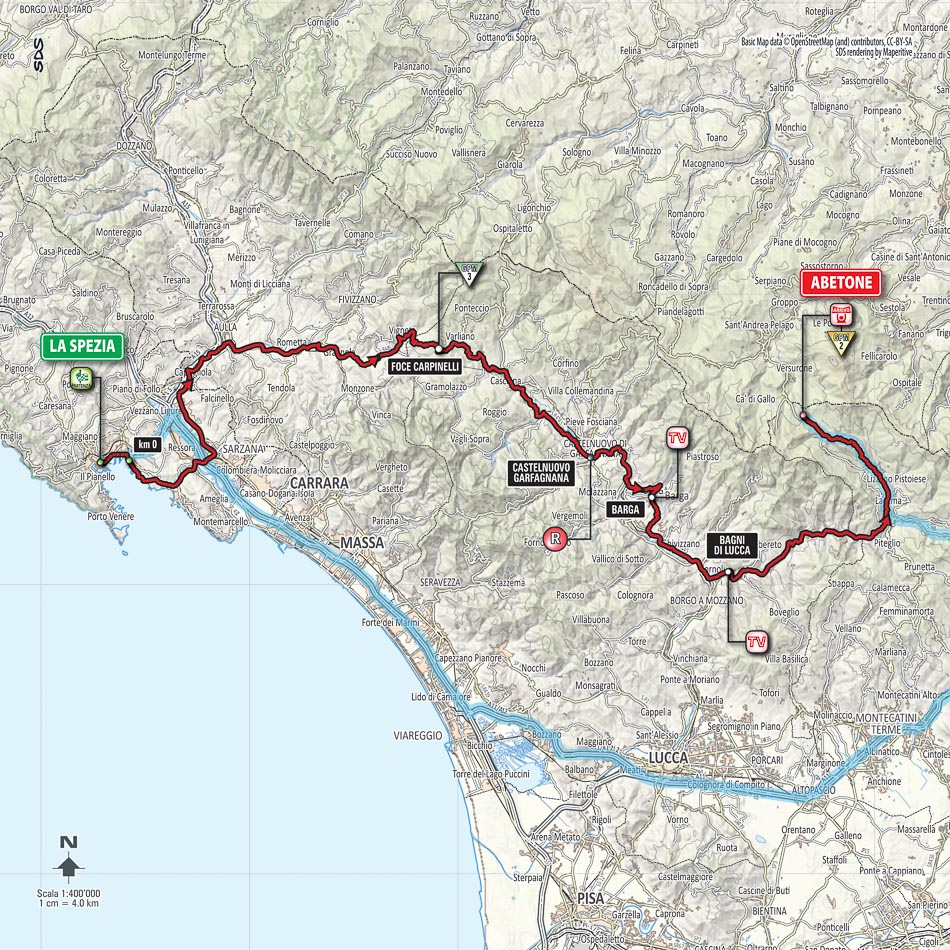

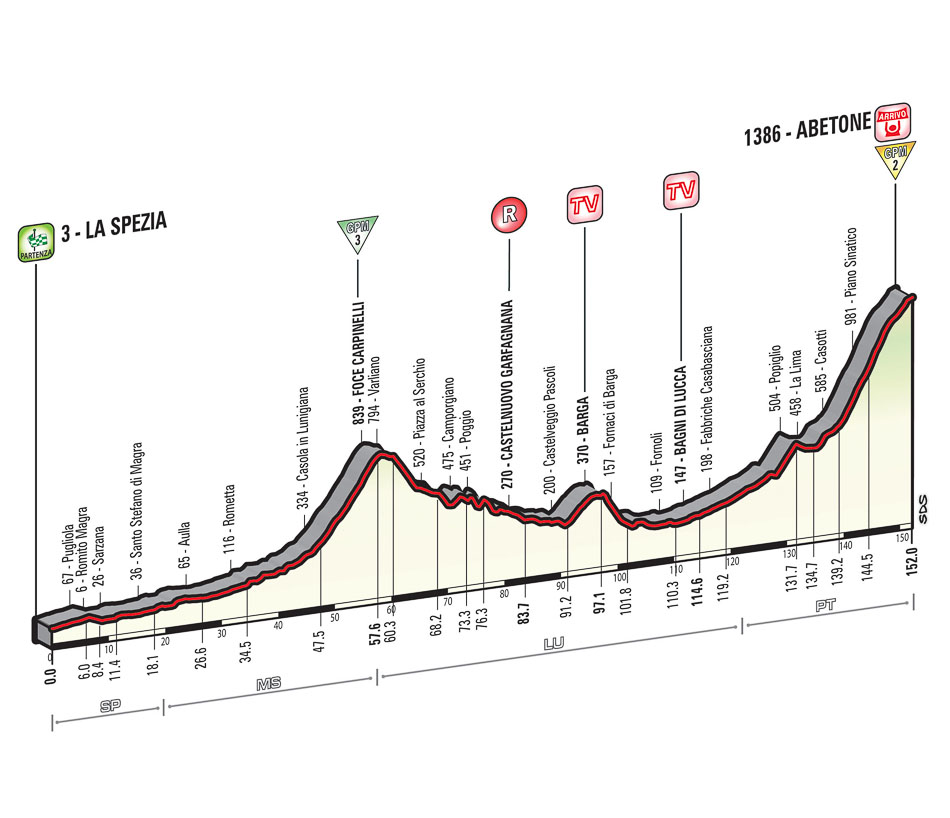

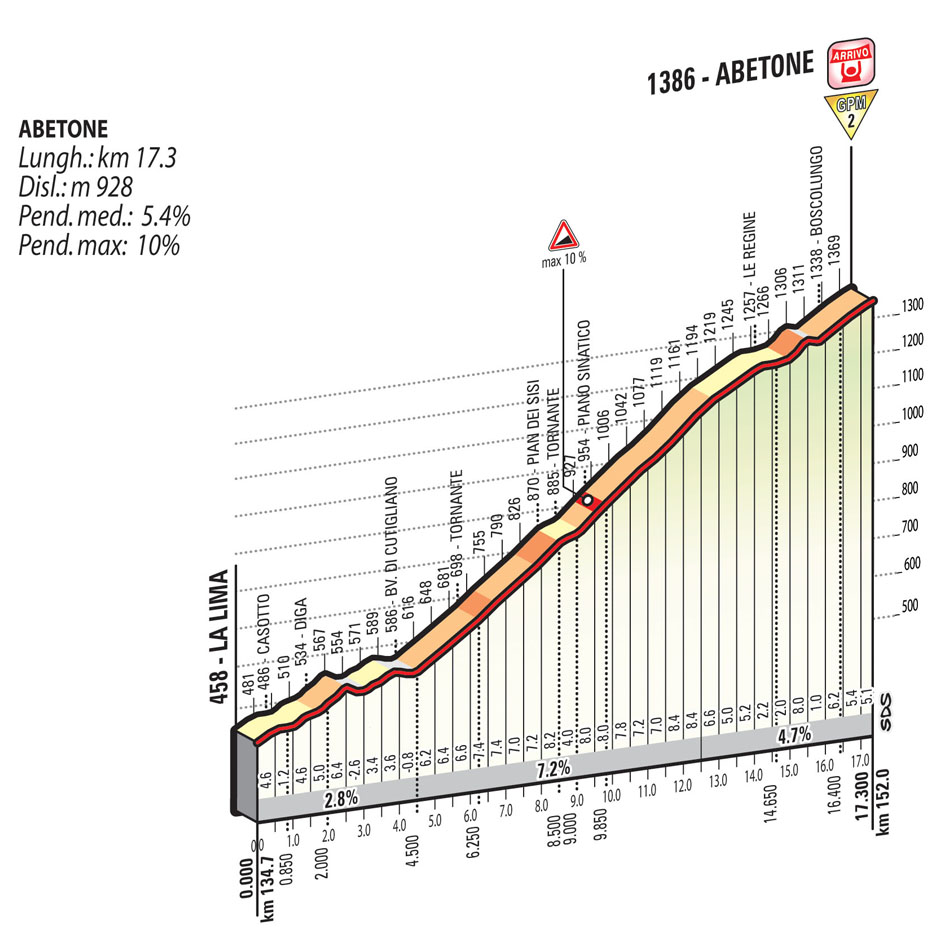

Stage 5, Wednesday May 13: La Spezia – Abetone, 152km (***)

The Giro d’Italia usually has its first uphill finishes early in the race but the organizers carefully chose the first climbs to make sure that they are not too hard and create too big time differences. That trend will continue in 2015 when the first summit finish again comes on the fifth day. This year the final climb is harder than the one that featured in the first two uphill finish in 2014 but with a pretty easy final part, it is unlikely to create any time differences between the biggest favourites.

Like the previous stages, stage 5 is a very short affair over just 152km that brings the riders from La Spezia to Abetone. It takes place almost entirely in Tuscany and is named after the Gino Bartali who was born in Ponte a Ema, and recalls his great success on virtually all mountains and, especially, his Abetone GPM wins in 1947 and in 1948.

The stage is quite short, and features just two “obstacles”, whose gradients are not too steep. The first part of the route is basically flat; past Aulla, the road starts to climb up to Foce Carpinelli (category 3, 10.1km, 5.0%, max. 9%) as the riders finally leave the coast to get to the first finish that is not at the seafront. Then it runs down to hit the short Barga climb and reach the foot of the final ascent (category 2, 17.3km, 5.4%, max. 10%).

The final 17.3-km climb starts in La Lima. Gradients only slightly exceed 2% over the first 4.5 km. The following 8 km are steeper, with gradients around 7%. The route then levels out slightly (5%) for the final 5km up to the finish on wide and well-surfaced roads. The final 3km have a pretty constant gradient of 4-5% but there is a very small descent with 1.5km to go. The uphill home straight, with a gradient of 5%, is 100-m long (on 5.5-m wide asphalt road) but there are no sharp turns on the winding mountain roads.

This is the stage that the GC riders have been looking forward to as it offers them the first chance to test their climbing legs on a longer climb in the finale. However, the easy nature of the final 5km means that it is not a day to make a difference and they will probably all head into the stage with a defensive mindset but if a rider like Domenico Pozzovivo has lost time in the team time trial, he may try an attack in the steep section like he did in the similar stage 9 last year. In general, summit finishes on 4-5% turn out to be a gradual elimination race and it often comes down to a sprint from a 20-30 rider group. If Michael Matthews has the climbing legs he had when he won the Montecassino stage in 2014, it may not be beyond his capabilities to win this one but the steep part may be a bit too long for him. The same goes for Simon Gerrans and Philippe Gilbert who will both try to survive and the stage is also tailor-made for Enrico Battaglin. Alberto Contador and Richie Porte will probably keep their powder dry for later but the stage may offer a chance for Rigoberto Uran to sprint to a few bonus seconds at the top. Depending on the situation on GC, there may even be a chance for a break to make it to the finish as bigger time gaps have now opened up and the stage has no obvious favourite.

Abetone has hosted a stage finish 3 times in the past, most recently in 2000 when Francesco Casagrande took a solo win with a 1.39 advantage over a 9-rider group of favourites that sprinted for second.

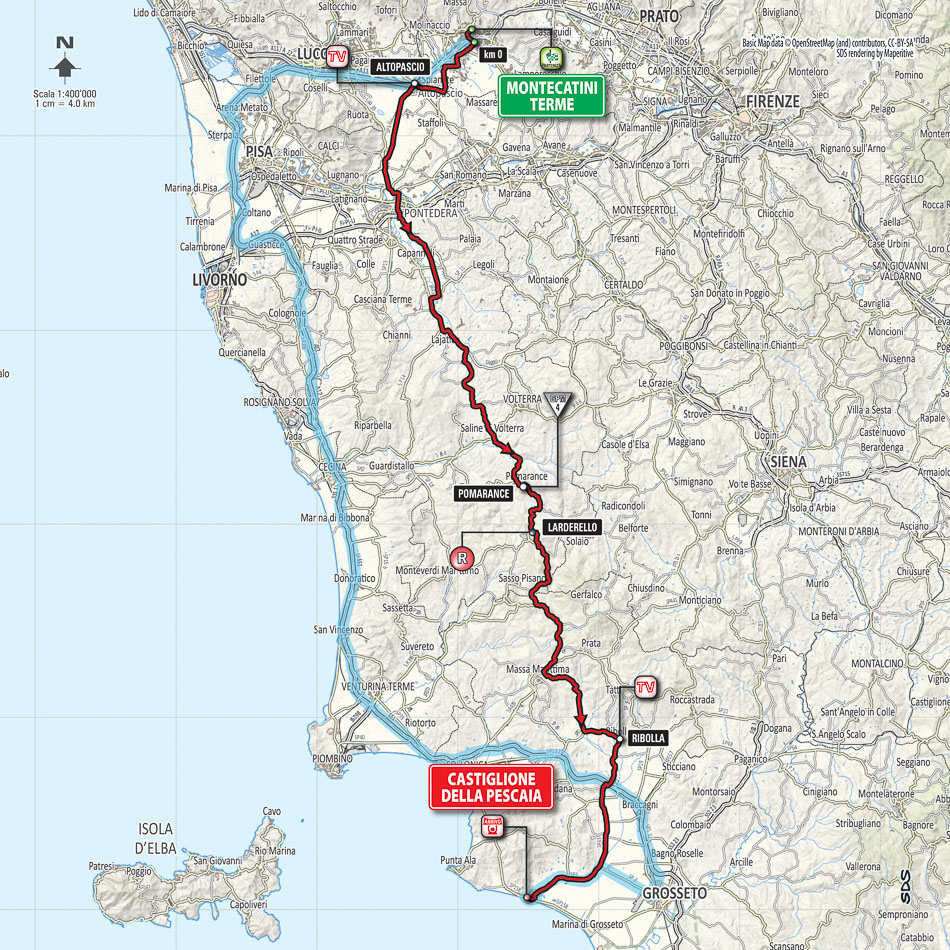

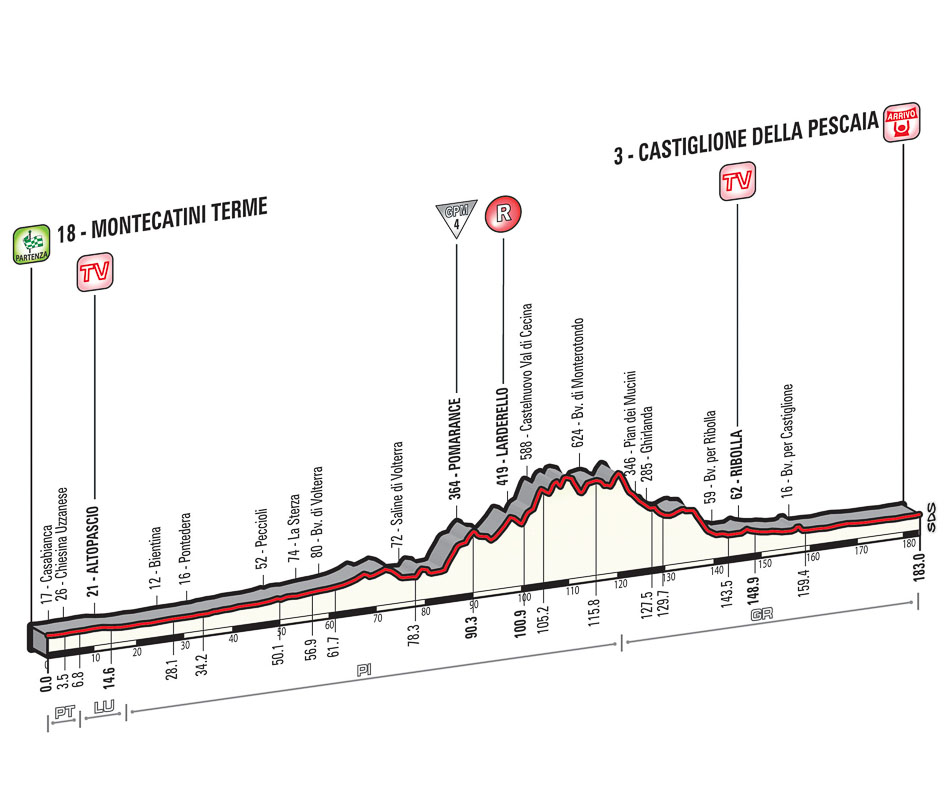

Stage 6, Thursday May 14: Montecatini Terme – Catiglione della Pescaia, 183km (*)

The first week has been a tough one for the pure sprinters who have not had a chance since the opening road stage on day 2. After three days of survival, it is finally time for them to get back into action on stage 6 which offers them their only other opportunity in what is a very lumpy and tricky first week of the race.

The stage is the longest in the first part of the race as it takes the riders over 183km from Montecatini to another coastal finish in the city of Castiglione della Pescaia. It is almost entirely flat, except for a short, central sector where the KOM climb is set. The first 80 km roll along mainly level roads across the Pisa territory as the riders travel in a southerly direction. Just past Saline di Volterra, the route reaches the Colline Metallifere (“Metal-bearing Hills”) and goes ahead, passing through Pomarance (category 4, 6.3km, 4.4%, max. 11%), Larderello (fixed feed zone) and Castelnuovo Val di Cecina. In this part, the course is undulating with several short climbs before the riders take on a long descent towards the coast. A final, level stretch leads to the finish, on largely straight roads.

The last 8 km on a perfectly flat road only feature two bends, 2.7 and 2.3 km from the finish, followed by a long, slightly bending stretch up to 1,000 m from the finish, where the home straight begins (on 7.5-m wide asphalt road). 1,500 m from the finish there is a speed bump that can be cleared following a straight trajectory. The final part is completely flat.

This stage may have a bit of climbing at the midpoint but the climbs come way too early to make a difference. With the final 40km being almost completely flat, this will be a very big goal for the sprinters who won’t miss a rare opportunity to go for glory in the first week. With a long flat finishing straight and a non-technical finale, this is a day for the really powerful sprinter who can reach the highest speeds.

Castiglione della Pescaia has never hosted a Giro stage before.

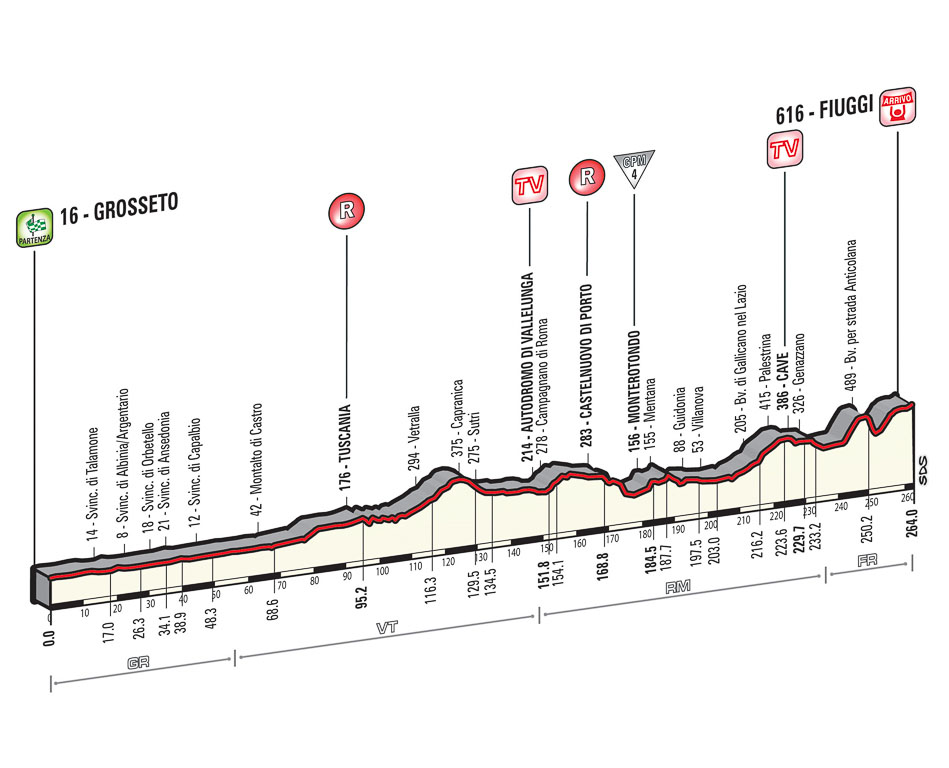

Stage 7, Friday May 15: Grossetto – Fiuggi, 264km (**)

The pure sprinters hopefully enjoyed stage 6 as it is back into the lumpy terrain for the tricky stage 7 which again offers a chance for the classics riders to shine in a tricky finale. At the same time, they will be familiar with the distance. The Giro d’Italia usually includes a very long stage of classics distance and the 2015 edition is no exception as this stage will cover a massive 264km.

The stage brings the riders from Grossetto past the capital of Rome and stays close to the coast as the riders continue the traditional southerly journey along the Tyrrhenian coast that typically characterizes the first part of the race. With its length of 264 km, it is the longest stage of the 2015 Giro. Its profile features no really challenging points, but the final part of the route is quite wavy. The first 70 km run along the Aurelia highway, the route then enters the Maremma region past Montalto di Castro. Rolling along gentle undulations, the route hits the towns of Tuscania and Vetralla, and skirts around the urban agglomeration of Rome. The KOM climb is set in Monterotondo, on top of a short spurt (category 4, 2.5km, 5.1%, max. 9%). After rolling past Tivoli (through the hamlet of Ponte Lucano), the peloton will be confronted with the last 60 km, wavier and more complicated (in terms of both course and profile) that lead to the finish in Fiuggi along Via Prenestina.

After the town of Piglio, some 15 km from the finish where the riders have just finished a short, uncategorized climb, a U-turn leads to a short descent (where the road is slightly narrower at points); from here, the stage course takes the new Via Anticolana. The last 10 km run gently uphill, first with a 4.4% average gradient. After crossing the Monte Porciano tunnel (672 m – straight and slightly uphill), 5 km from the finish, the route reaches Via Prenestina through large, well-paved roads, still climbing slightly at a 1-2% gradient. Upon entering urban Fiuggi, the road turns left, and climbs at a gradient of approx. 2% up to the last kilometre, where the route becomes slightly steeper. The home straight is 350-m long, on 7-m wide asphalt road, with a gentle 3-4% gradient. The finale is mainly non-technical as there will only be some sweeping bends inside the final 3km before the riders turn left in a roundabout with 1300m to go. There are two sweeping bends in quick succession, leading onto the short finishing straight.

With the final 10km on a slight rise, this is not a day for the pure sprinters and instead the stage is tailor-made for Michael Matthews who has emerged as the world’s best uphill sprinter on such gradients. Depending on the outcome of stage 3 and 5, the Australian may even be leading the race at this point and will have a great chance to win another stage in the maglia rosa. However, everybody will be looking at Orica-GreenEDGE to control the stage and they are likely to have been doing a massive amount of work in the early part of the race. It is a massive task to ride on the front for 264km and the team may be willing to let a break ride away with this one. If Bardiani, Androni, CCC or Southeast miss the break, however, they may be eager to set up a sprint as they all have riders that excel in this kind of uphill finish.

Fiuggi has hosted a stage finish 8 times in the past, most recently in 2011 when Francisco Ventoso beat Alessandro Petacchi in a memorable uphill sprint that left both riders completely exhausted.

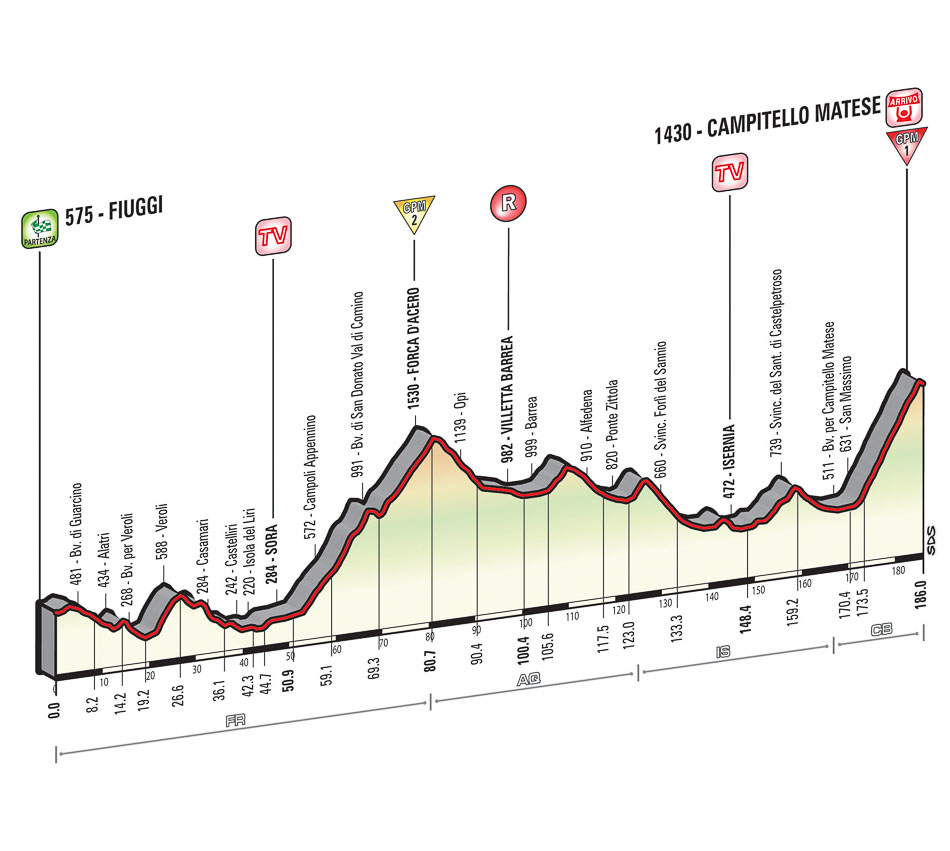

Stage 8, Saturday May 16: Fiuggi – Campitello Matese, 186km (****)

The Giro d’Italia has often had the first major summit finish on the second Saturday in the race and this year it will again be the 8th stage that offers the GC riders the first bigger chance to make a difference. Like the previous summit finish in stage 5, the final climb to Campitello Matese is not overly tough but is so steep that there will no longer be any reason for the climbers to hold anything back, with the long time trial looming in the horizon.

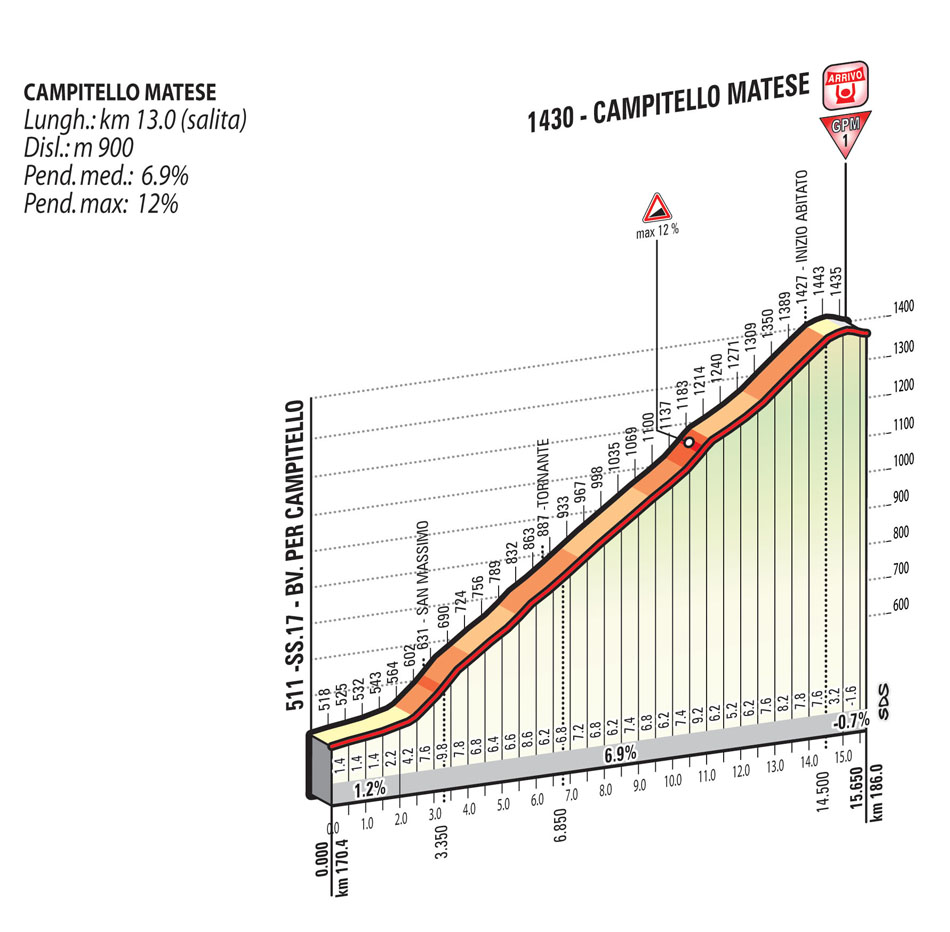

The 186km start in Fiuggi and finishes at the top of the category 1 climb to Campitello Matese as the riders now start their journey from the Tyrrhenian to the Adriatic coast before they turn around and head back towards the major mountains in the northern part of the country. This mountain stage is marked by the lengthy climbs of the two KOMs: Forca d’Acero (category 2, 26km, 5.0%, max. 9%) and Campitello Matese (category 1, 13.0km, 6.9%, max. 12%).It is a long, very regular climb with no really steep parts and a short descent at the midpoint. After the start, the route hits Alatri, Veroli and Sora on largely flat roads. This is where the long Forca d’Acero climb begins, leading first to Abruzzo, and then fast to Molise (past Ponte Zittola). A long and easy-to-ride descent leads to Isernia along the new ss. 17 expressway, which features a series of tunnels. Past Isernia, a further stretch on wide and slightly hilly road leads to the final Campitello Matese climb.

The final climb is over 15 km in length. After the first deceptive false-flat drag, the route gets to the town of San Massimo (the last urban centre before reaching the finish) with gradients of approx. 10%, then it takes the road leading to the finish (large, well-surfaced and with wide hairpin bends extending up to 1 km from the finish). It is very regular with an constant gradient of 6-8%. The steepest 10% section comes just after the 3km mark. Starting from the last kilometre, the road descends slightly up to 250 m from the finish. Here the road levels out on the home straight, on 6.5-m wide asphalt road. There are two hairpin bends just before the flamme rouge and then a sweeping right-hand turn 250m from the line.

This stage is the first really big opportunity for the climbers who will be eager to battle it out on the final climb. It doesn’t include any very steep sections but a long regular climb of 6-8% is usually enough to create some differences even though they are unlikely to be very big. With the long time trial still to come, riders like Fabio Aru and Domenico Pozzovivo will have to take this opportunity and they may also want the bonus seconds to come into the play. Alberto Contador also wants to stamp his authority on the race and as the first summit finish is usually decided by the favourites, this should be won by a GC rider. As it is not a big mountain stage, however, there is a chance that a break will make it to the finish as it is often the case in Giro d’Italia mountain stages.

The final climb has hosted a stage finish 6 times in the past, most recently in 2002 when Gilberto Simoni held off Francesco Casagrande and a small group of favourites by 4 seconds. He was later disqualified due to a positive doping test and the UCI has decided not to award the stage win to another rider.

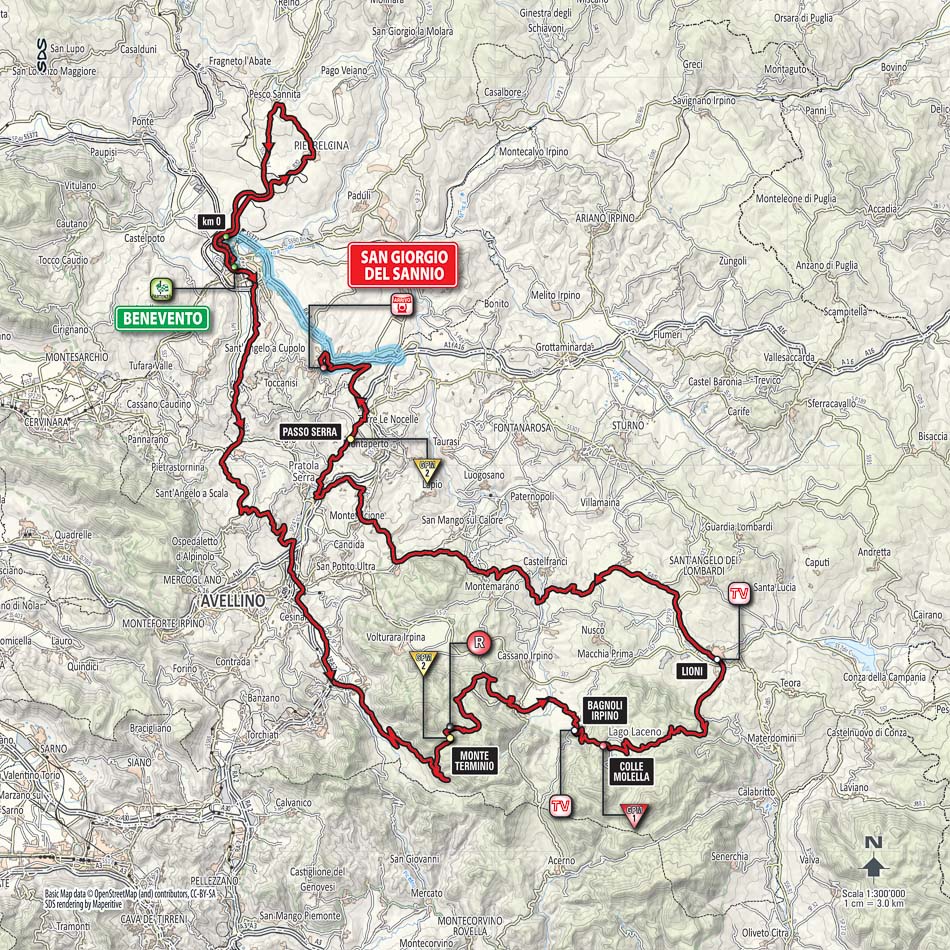

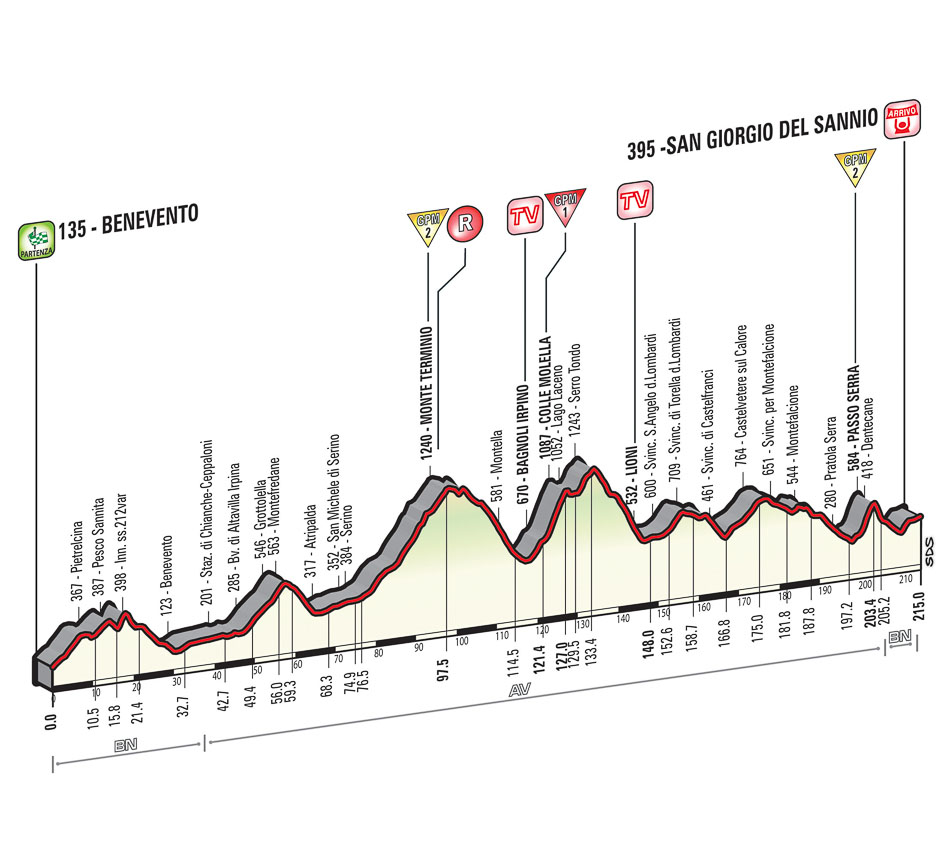

Stage 9, Sunday May 17: Benevento – San Giorgio del Sannio, 215km (****)

The riders are now looking forward to their first rest day after a long first week of very hilly racing but first they have to get through another hilly ride in the Apennines. The start and finishing cities are located very close to each other but the riders will have to do a tough loop in the mountainous area that includes almost no flat roads.

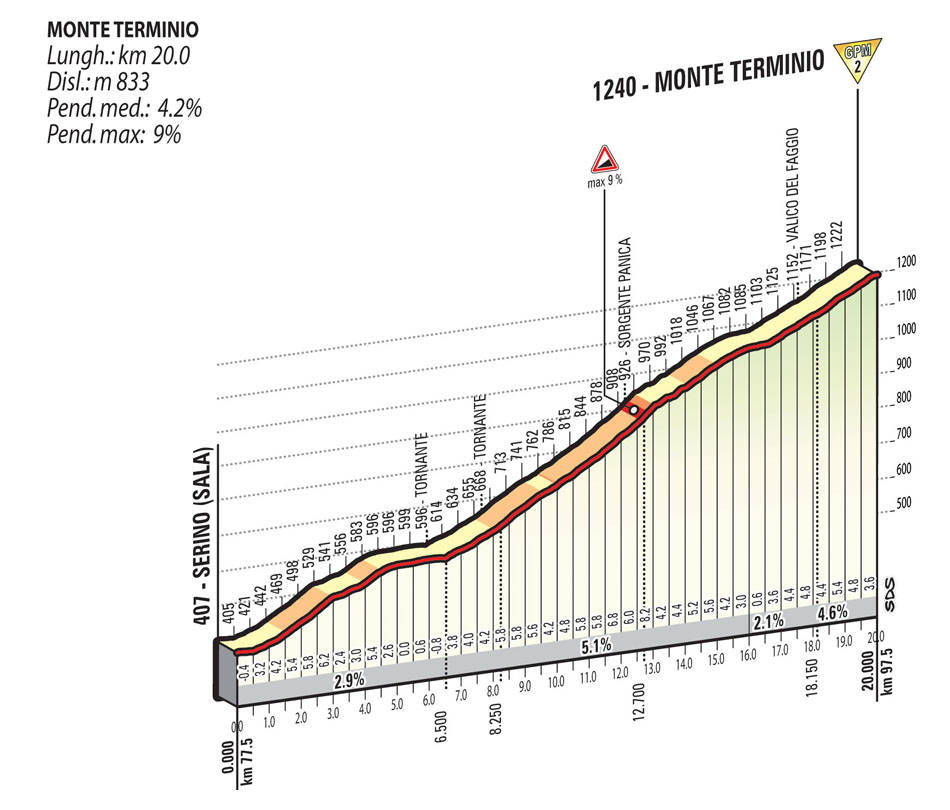

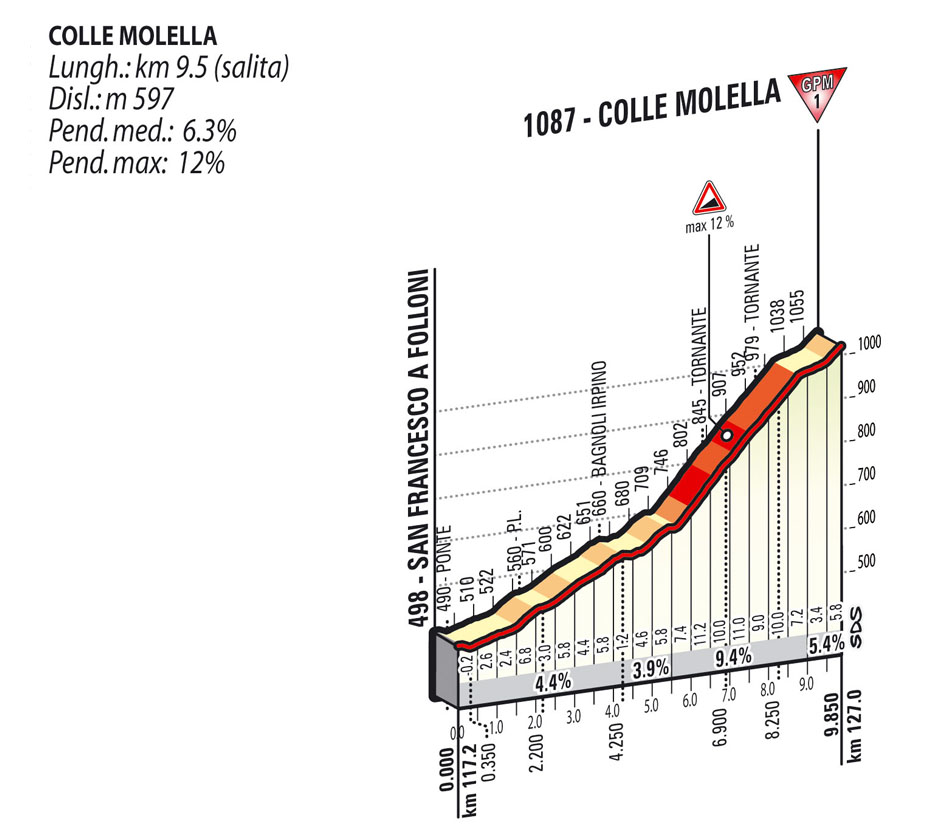

At 215km, it is the second stage with a distance of more than 200km and brings the riders from Benevento to San Giorgio del Sannio. It is a very wavy stage, with a total difference in altitude just under 4,000 metres. The first, wavy and rough part of the route rolls across the Benevento area, hitting Pietrelcina, Benevento and Atripalda. Here the course enters the Irpinia region, with a long and easy-to-ride climb up Monte Termino (category 2, 20.9km, 4.2%, max. 9%) with no really steep sections, preceding the more challenging Colle Molella (Lago Laceno) ascent (category 1, 9.5km, 6.3%, max.12%) where Domenic Pozzovivo won a stage in 2012. This climb has a very easy first part but then includes a brutal section with a gradient of 9-12% over 2km before it levels out near the top. The route then follows the constant undulations that lead through Lioni, Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi and Castelvetere sul Calore, up to 20 km from the finish, where the harsh Passo Serra climb (category 2, 3.6km, 8.0%, max. 13%) will lead to the final kilometres of the stage. The road surface is worn out (and narrow at points) over some sectors.

The Passo Serra climb has a really demanding central sector, reaching double-digit gradients. The summit is located 11.6km from the finish. A short, brisk descent follows, up to 5 km from the finish. Another short climb of 2km with a 4.9% gradient and a stretch on flat city roads precede the 600-m long home straight (on 7-m wide asphalt road), with a 3% gradient. The finale is pretty technical as there are several turns between the 3km to go mark and the flamme rouge. The final two turns come with 1.2km and 0.6km to go respectively.

This stage has breakaway written all over it. The hilly terrain makes it almost impossible to control and as the finale is not hard enough for the GC riders to make a difference, the major teams will be keen to get safely to the rest day. This means that the strong stage hunters who can survive this kind of tough climbing have marked this one out a big goal and we should see a very aggressive start to the stage. There is always a chance that a team which has missed the break, will chase it down but in this kind of terrain and with more opportunities still to come, it is unlikely to happen. A strong escape group is likely to decide the stage in the hilly finale where a strong climber will emerge as the stage winner.

San Giorgio del Sannio has only hosted a stage finish once, in 1987 when Rosoli took the win.

Rest day, Monday May 18

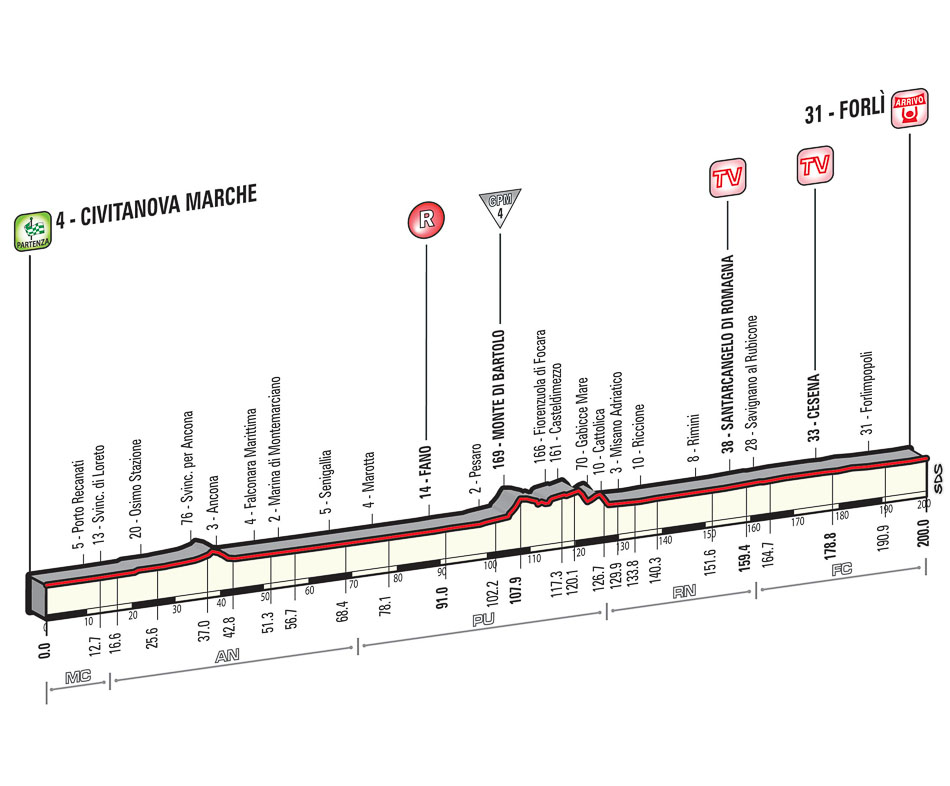

Stage 10, Tuesday May 19: Vicitanova Marche – Forli, 200km (*)

The first week was a frustrating one for the sprinters who only had two chances during the first 9 days, and so they will be glad to know that the 6-stage second week offers them another two opportunities. The first comes on the day after the rest day which should also provide the GC riders with a good opportunity to get back into the racing rhythm without any big dangers.

The second week of the Giro usually starts with a long northerly run to the mountains in the north and often has a completely flat stage along the Adriatic coast. This year that stage comes on day 10 when the riders travel over 200km from Vicitanova Marche to Forli. The stage is entirely flat, and covers almost the whole of the Adriatica coastal road. The route unfolds along wide and largely straight roads for 100 km, with just a brief detour to climb up Monte di Gabicce (category 4, 4.8km, 3.5%, max. 9%) from the Pesaro slope. The following 60 km run straight along the ss. 9 Via Emilia, through Santarcangelo di Romagna, Cesena and Forlimpopoli, leading to the finish in Forlì.

The last kilometres past Forlimpopoli run along straight roads, with roundabouts and traffic dividers being the main obstacles typically found in urban areas. Approx. 2 km before the finish, there is a 1,500-m setts paved sector, with a bend 1,100 m from the finish (Piazza Saffi) and a bottleneck 800 m from the finish. The route features one last bend 500 m before the finish. The home straight is on level, 7-m wide asphalt road.

There is no chance that the sprinters will miss this opportunity and this Adriatic coast stage is often a very calm and relaxed ride in usually sunny conditions. However, it will all heat up in the finale where the lead-out trains will gear up for the tricky finale. With the final two turns coming in quick succession and leading onto a very short finishing straight, positioning will be crucial and team support decisive and we can expect a big sprint between the sprint teams to get to the first of those two turns in the first position. Then it will be left to the best-placed sprinters to battle it out for the win in Forli.

This is the 9th time a stage has finished in Forli. It last happened in 2006 when Robbie McEwen beat Olaf Pollack in a bunch sprint, with the German taking over the leader’s jersey from his teammate Serhiy Honchar.

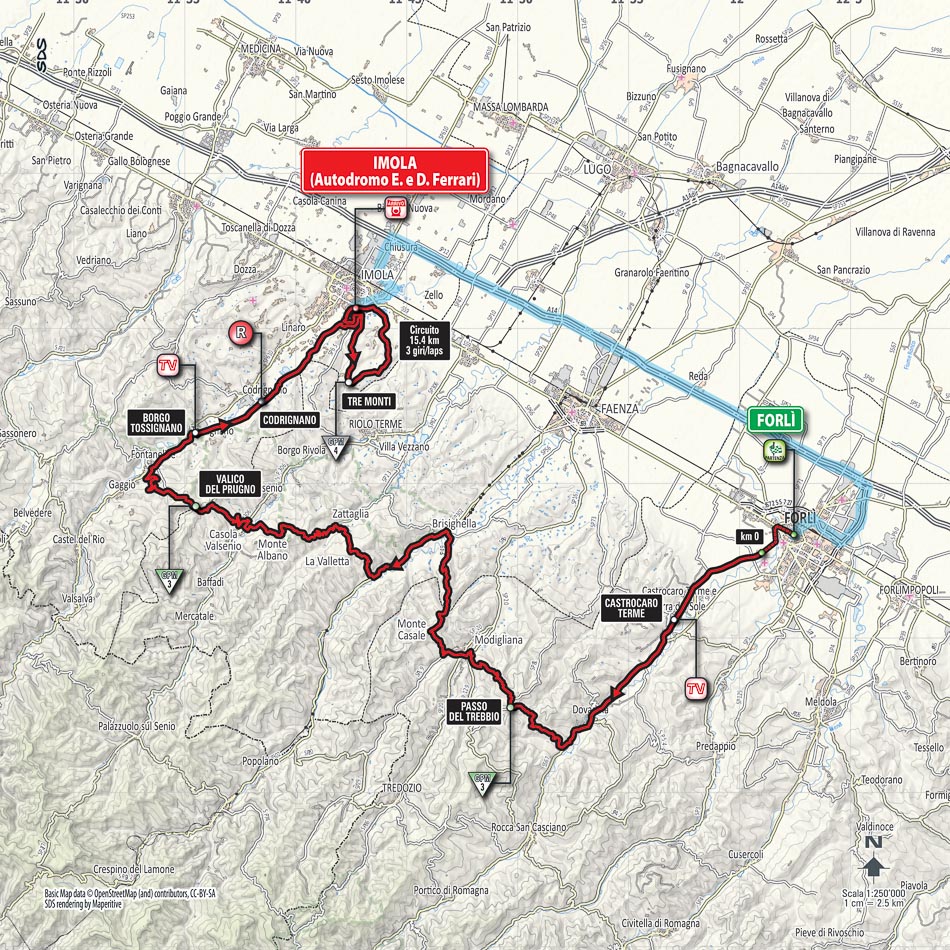

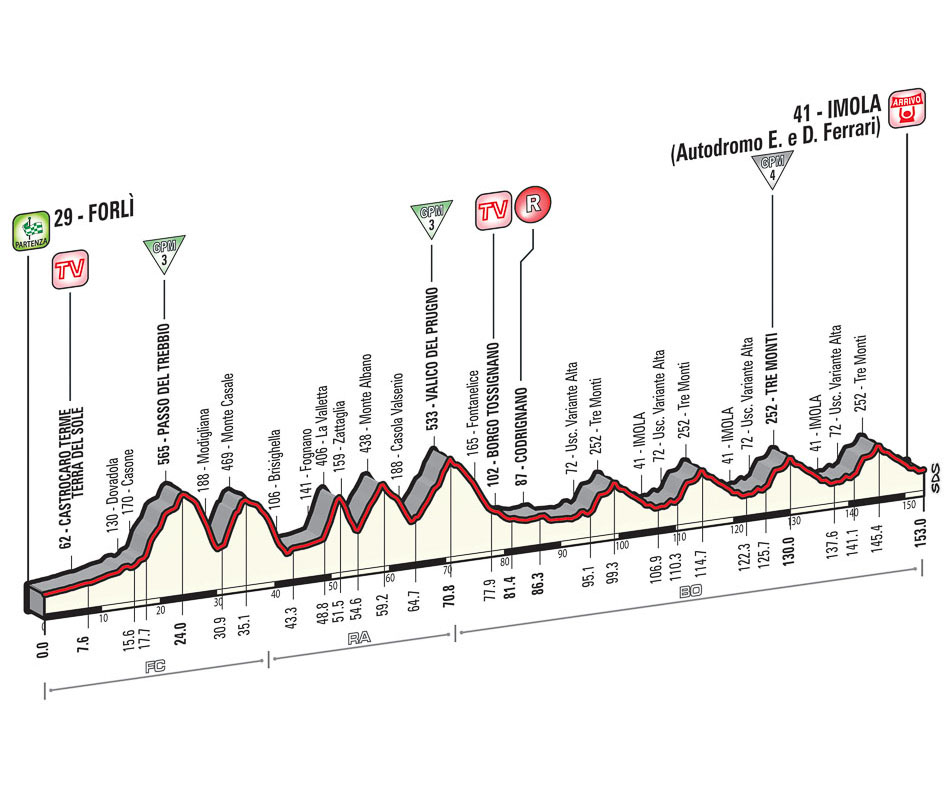

Stage 11, Wednesday May 20: Forli – Imola, 153km (***)

The journey towards the mountains in the north continues at the midpoint of the race but unlike in the previous stage, the sprinters won’t get an easy ride along the coast. Instead, the riders will head into the hills for a lumpy, tough ride that has very little flat roads and is a very typical Giro d’Italia stage.

Like many of the other moderately hilly stages in this year’s Giro, stage 11 is a pretty short affair over just 153km that brings the riders from Forli to Imola and a finish on the famous Autodromo in the city. The stage is short, yet quite challenging, marked by 5 short but hard-going climbs before entering the final circuit (the Tre Monti circuit), to be covered three times. The route takes in these climbs one after another, and never flattens out: Trebbio (category 3, 6.3km, 6.3%, max. 11%, hardest at the bottom), Monte Casale (with a first section of 10.1% before it levels out in the second half, La Valletta (a 2.7km ascent with an average gradient of 9.8% and a maximum of 14% at the midpoint, Monte Albano (a 4.6km climb with a constant gradnt of 6-7%) and Valico del Prugno (category 3, 5.6km, 6.2%m max. 9%, very regular). Then it reaches the Imola racetrack and enters the final circuit, at the exit point of the “Variante Alta” chicane.

The final 15.4-km circuit is raced partly on the Imola racetrack, and partly outside it. From the finish line (on the pit straight), the route covers around 3.5 km of the track, up to the “Variante Alta”. Here, the stage course leaves the racetrack (bottleneck), takes the climb leading to Tre Monti (category 4, 4.4km, 4.1%, max. 10%, KOM points will be awarded upon the third pass over the summit) then descends onto quite wide and well-paved roads until the last km, that leads to the entry point of the Rivazza turn, around 850 m before the finish. The route features one last bend 650 m from the finish, and a long, slightly bent home straight on an 8-m wide, perfectly level tarmac surface. In general, there aren’t many technical challenges in the final part of the course.

This is the kind of short, lumpy stage that is very likely to be won by a breakaway. The first part of the stage is extremely hard and as there will be a big fight to join the early break, it could turn out to be a very demanding affair. Many riders are likely to be sent out the back door but when the break has taken off, a regrouping will take place. The finishing circuit is not very difficult though and if an ambitious home team has missed the break, they may try to bring it back together. In that case, it may come down to a sprint from a reduced peloton for the strongest sprinters and classics riders but the stage is most likely to be one for the escapees who need to be very strong climbers to make the break in the hilly first part.

Imola has hosted a stage finish twice in the past, most recently in 1992 when Pagnin won the stage.

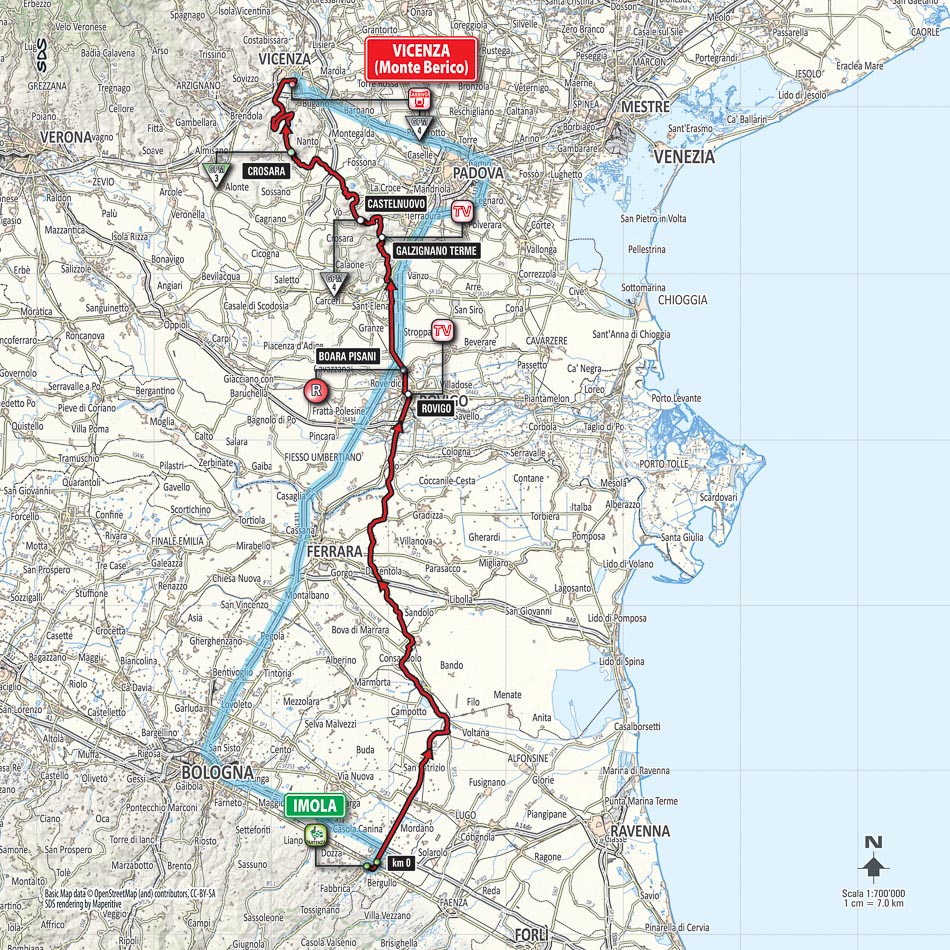

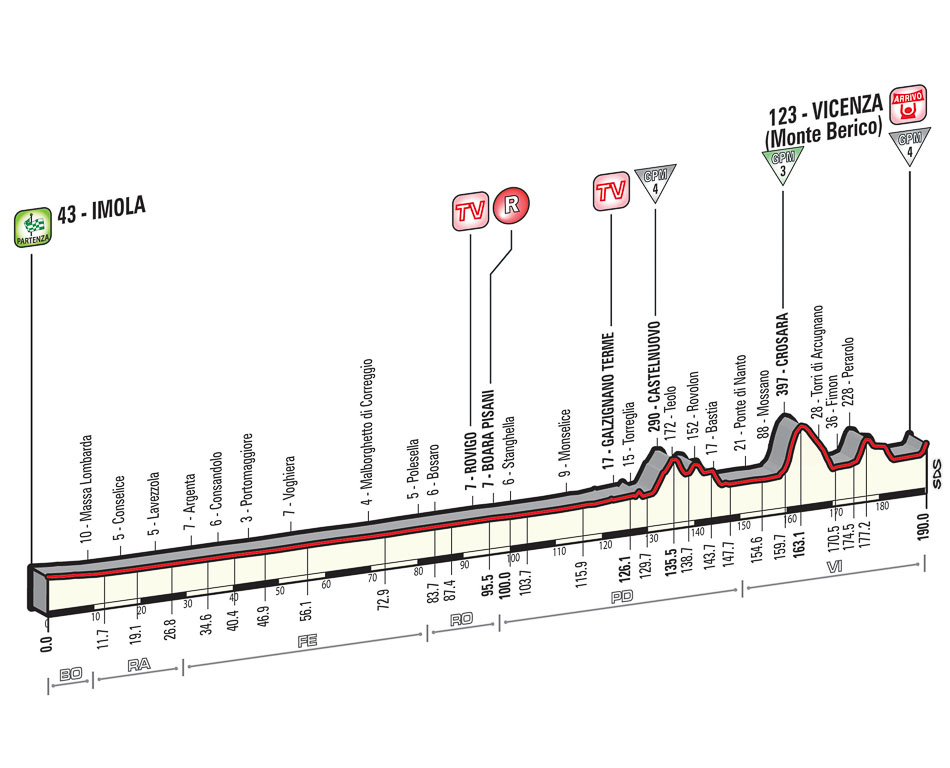

Stage 12, Thursday May 21: Imola – Vicenza, 190km (***)

The Giro d’Italia and Vuelta a Espana are famously known for their uphill finishes on short, sharp walls that always produce a great spectacle. This year’s Italian grand tour again offers this kind of punchy finale even though the short Monte Berico in Vicenza is not one of those incredible steep climbs that have often featured mainly in the Vuelta a Espana. The short climb will be the scene of an exciting battle at the end of the 12th stage.

The stage has a length of 190km and brings the riders from Imola to Vicenza. It is clearly divided into two parts: the first 130 km across the Po Valley are totally flat, while the last 60 km are very wavy and rough, with a few demanding climbs, and a mountain finish after a final spurt. The route runs across the Basso Ferrarese region and the Polesine area, along flat, largely straight and regular-width roads, worn out at points. Just past Torriglia, the route takes in the easy-to-ride Castelnuovo climb (category 4m 5.4km, 5.0%, max. 11%), in the Euganean Hills, and then crosses a short sector of flatland leading to the Berici Hills. The course clears the Crosara climb (category 3, 3.7km, 9.1%, max. 17%), going up from the Mossano slope, with almost 2 km at gradients exceeding 10% and peaks reaching as high as 17% in the first half, on quite wide roads leading to the technical Lapio descent and, eventually, to the challenging final 15 kilometres.

After Fimon, the route takes in a 2-km climb, with an 8-9% slope, peaking as high as 11% at points near the top. Then comes a short false-flat drag, followed by a demanding – yet short – descent, leading to the last 5 km, which run entirely on flat terrain up to 1,200 m from the finish, where the final spurt begins. The last km has an average 7.1% gradient, with slopes approaching 10% in the final part and topping out at 11% in the very last stretch of the spurt. The home straight is 300-m long, on 7-m wide asphalt road. After the descent there are no major technical challenges as the road just includes sweeping turns inside the final kilometre.

If he had been in this race, Joaquim Rodriguez would have this stage a big target as it would offer him a perfect chance to win a stage and pick up important bonus seconds. However, none of the major GC riders in this race excel in this kind of punchy finish and so most of them will be keen to get safely through the day. There is a big chance that a breakaway will make it to the finish as there are not many real specialists for this kind of stage and much will depend on Orica-GreenEDGE and BMC. With the easy first part, it is definitely possible to control an early break but the final part of the climb may be a bit too steep to suit Michael Matthews and Simon Gerrans perfectly. Furthermore, the climbs in the finale are very tough and if those teams bring things back together for the finale, there is a big chance that a late break can finish it off. We may even see a few GC riders give it a go on the final climb and with the technical descent, it will be possible to stay away, especially if it is wet. If Carlos Betancur has ridden himself into form at this point, the stage has his name written all over it and it could be an objective for the Ag2r team. This stage can be won by an early breakaway, a late attack or in an uphill sprint from a reduced group.

Vicenza has hosted a Giro finish 9 times in the past, most recently in 2013 when Giovanni Visconti attacked on a late climb and managed to hold off a small peloton that was led home by Ramunas Navardauskas. The finale on Monte Berico was used in 1967 when Spaniard Francisco Ibarra Gabica took the win.

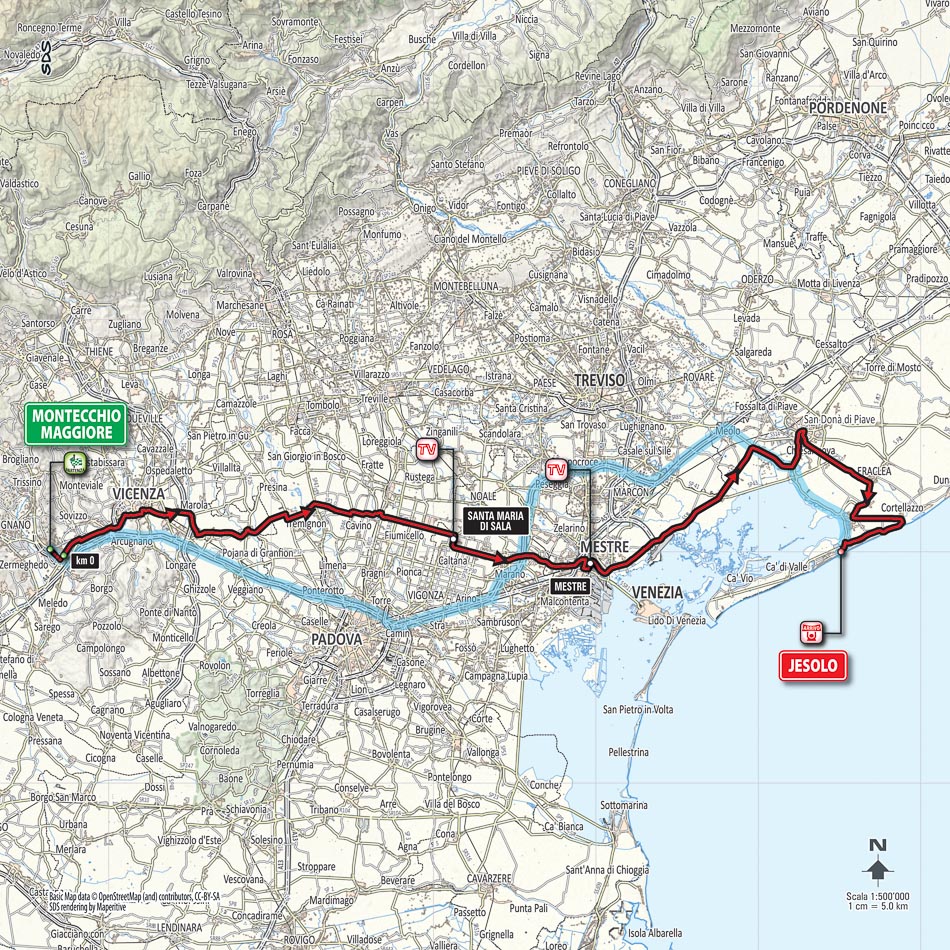

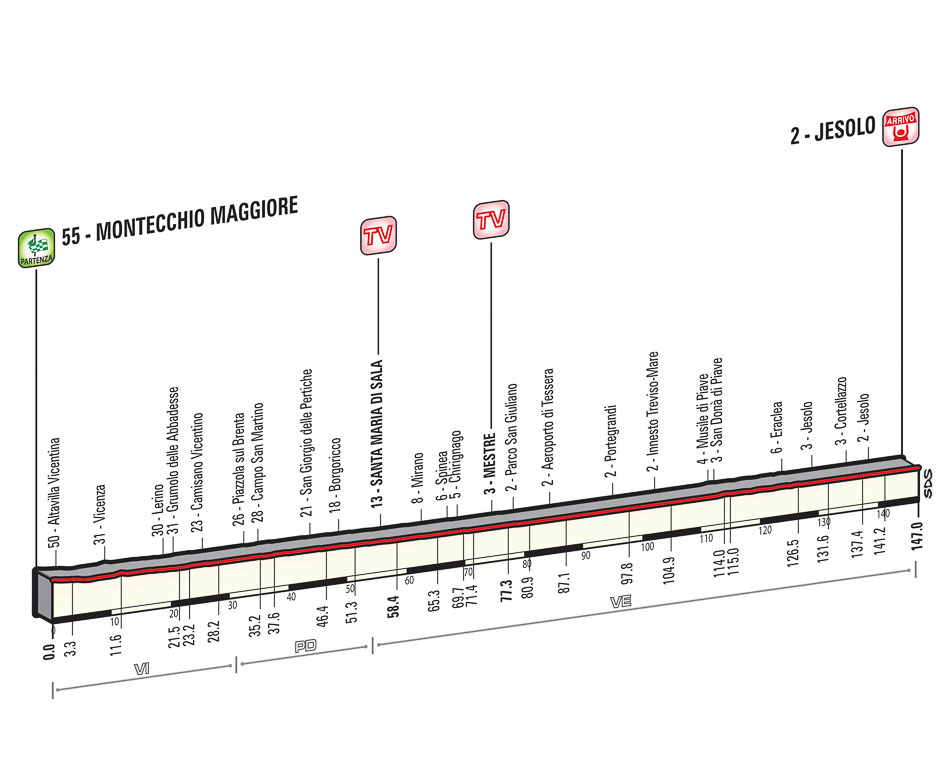

Stage 13, Friday May 22: Montecchio Maggiore – Jesolo, 147km (*)

Italy may be known for its hilly terrain but it also includes one of the flattest parts of Europe. The Po valley includes no topographical challenges at all and makes it possible for the Giro organizers to design stages that are flatter than what can be found in the Tour de France and the Vuelta a Espana. The 2015 edition of the race will such a stage on day 13 which will give the sprinters their second and final chance in the second week and the GC riders an easy day one day before the crucial time trial.

The organizers have made the wise decision to make the stage a short one as the easterly run from Montecchio Maggiore west of Vicenza to Jesolo is only 147km long. It is one of the shortest stages of the Giro, and it is also entirely flat. The route runs across the Venetian Plain, from Montecchio Maggiore through Vicenza, Piazzola sul Brenta, Mirano, Mestre, and Musile di Piave to Eraclea, where the final 20km begin. The riders have to watch out for a number of obstacles, such as roundabouts, speed bumps and traffic dividers, while crossing urban areas.

The stage has a fast-running finale on level roads. After crossing the Piave River in Eraclea, the route first hits the city of Jesolo and then reaches Cortellazzo via the road that rolls along the riverbank. Here in Cortellazzo, the road turns right onto a bridge with narrowed roadway. The stage course then takes wide, flat and straight roads (“sprinkled” with roundabouts with different diameters) that lead to the finish line. The home straight is approx. 500-m long, on 7-m wide asphalt road. The penultimate kilometre has two roundabouts before the riders turn left in the final roundabout with 500m to go. In the finale, the flat road bends slightly to the right.

This stage has bunch sprint written all over it and there is virtually no chance that it won’t be a day for the sprinters. Everybody knows this and so it will probably be a pretty leisurely ride with a small breakaway getting some attention before the peloton speeds up in the finale. Lead-outs and team support will be very important in this technical finale where it will be very important to be well-positioned before the final three roundabouts and positioning may be just as crucial as actual speed.

Jesolo has hosted a Giro d’Italia stage finish 4 times in the past, most recently in 1988 when Di Basco took the win.

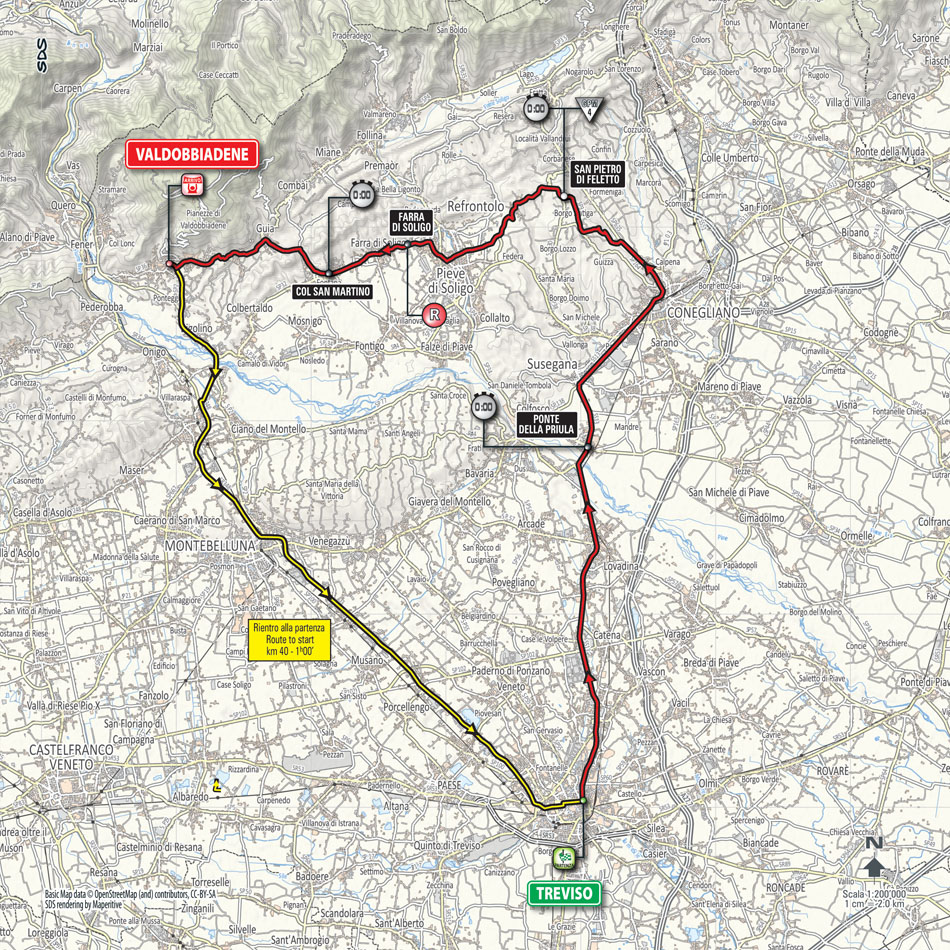

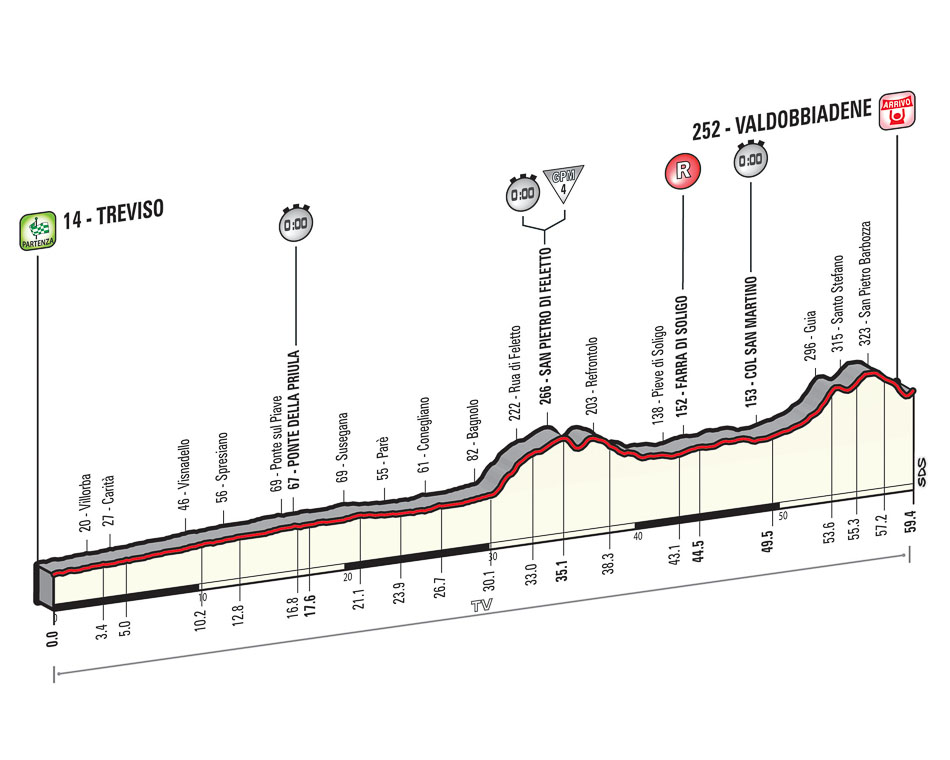

Stage 14, Saturday May 23: Treviso – Valdobbiadene, 59.4km ITT (*****)

When the course for the Giro d’Italia was announced, one stage got more attention than the others. The very long 59.4km time trial on the fourteenth day may turn out to be more important than any of the mountain stages as massive time gaps can be opened in such a long time trial. In the past, the Giro d’Italia has often had limited time trialling as the Italians have often had a hard time in this discipline but in recent years, the organizers have included longer flat TTs in an attempt to attract more international stars. In 2013, the inclusion of a 54.8km time trial was one of the main reasons for Bradley Wiggins’ participation and last year the 42.2km time trial in the Barolo district made the course more versatile than usual.

However, the long time trials in the Giro d’Italia are never flat and the organizers always seem to find some scenic routes that include a combination of tough climbing, technical sections and flat power stretches. This year’s course is no exception and even though the specialists will find the first part to their liking, the climbers will be pleased to know that the second part is much more suited to their skills.

The stage brings the riders over 59.4km from Treviso to Valdobbiadene. The long and challenging time trial stage is raced against the background of the Prosecco vineyards. It can be clearly divided into two halves. The first 30 km, from Treviso to Conegliano, run along level, wide and straight roads, with a few roundabouts in between. The following 29.4 km are indeed challenging, with a climb (category 4, 4.9km, 3.8%, max. 9%) just past Conegliano, and an ever-undulating route, winding its way across the hills on narrow yet excellently surfaced roads. The climb is not very steep and only includes a short 500m section with a gradient of more than 8% on the lower slopes before it levels out. The final 2.5km only have a gradient of 1-3%. In the finale, there’s a long gradual uphill before the riders get to a 6km climb. Again it only includes a steep section of around 7% at the midpoint and otherwise it is a gradient of 1-3%.

The last 3 km run downhill up to 400 m from the finish. A challenging left-hand bend 750 m before the finish is followed by a right-hand bend with 500 m to go (still in the downhill sector). 400 m before the finish, the last bend leads into the home straight: 400 m with a 5.5% gradient, on 6-m wide asphalt road.

The Giro d’Italia may traditionally be won in the mountains but this year the most important stage is likely to be the time trial. This is the day that Richie Porte and Rigoberto Uran have red-circled as the one where they can build a race-defining advantage and if they are on a good day, they can gain a massive amount of time in this stage. Alberto Contador has had mixed experiences in time trials and while he will probably suffer in the first half, he is likely to be strong in the second part. The same goes for Domenico Pozzovivo who has done some amazing time trials on hilly courses in the past while it will be all about limiting the losses for Fabio Aru. With none of the biggest specialists at the start and the final part being pretty tough, the stage is likely to be won by a GC rider and it would be no surprise to see either Uran or Porte on the top step of the podium at the end of stage that suits their versatile skills perfectly.

Valdobiaddene has only hosted a stage finish once. In 2009, race leader Mark Cavendish crashed in the finale and it was Alessandro Petacchi who made it two in a row in his home race by beating Tyler Farrar and Francesco Gavazzi in an uphill sprint to take the jersey off Cavendish’s shoulders.

Stage 15, Sunday May 24: Marostica – Madonna di Campiglio, 165km (****)

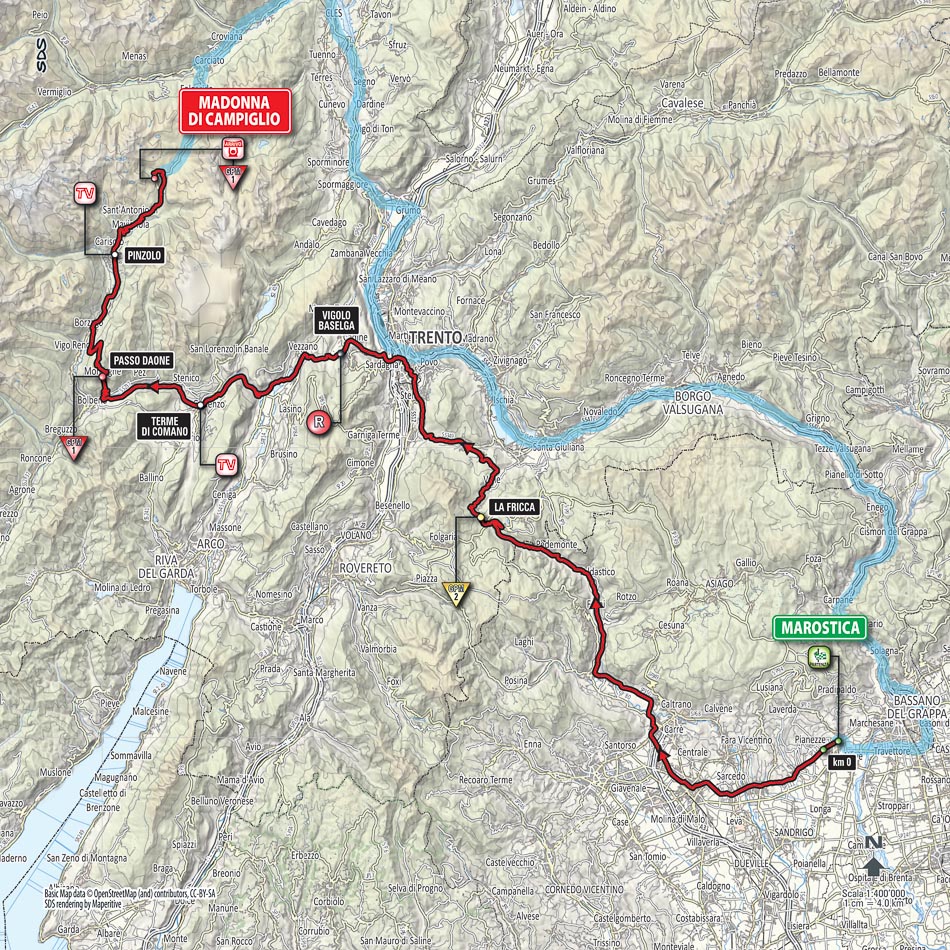

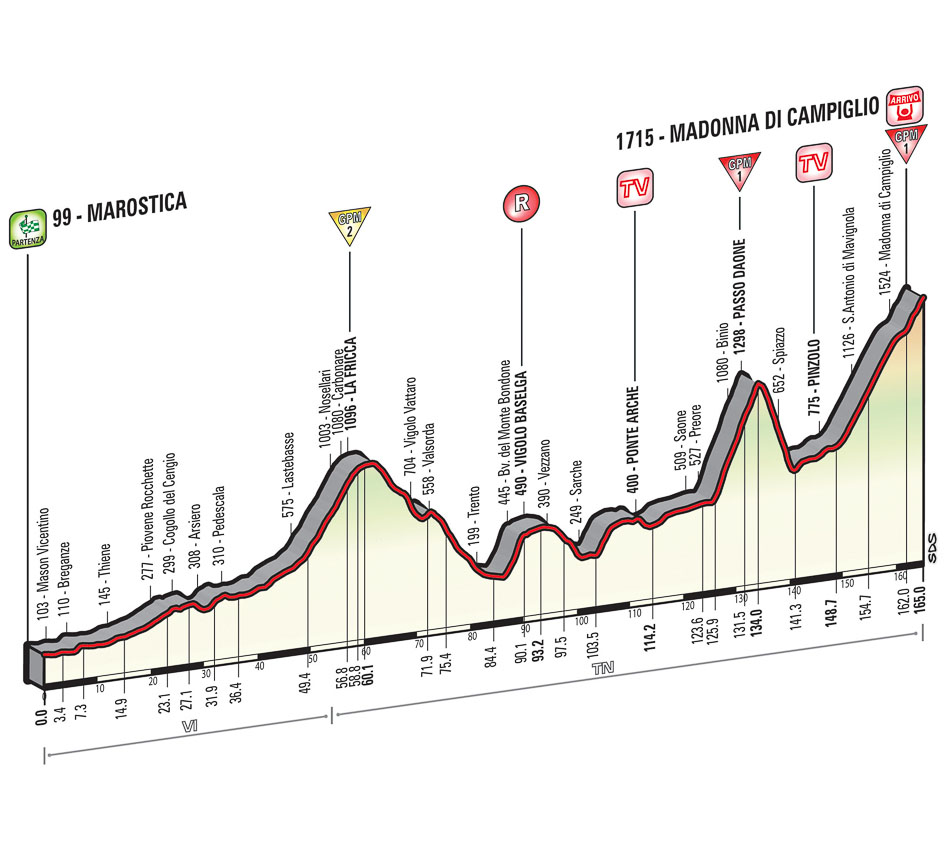

The climbers are likely to have been dealt a blow in the time trial but they will be given an immediate chance to strike back in the tough stage 15. After their long journey from the Ligurian coast to the south of the country and back to the north, the riders have finally reached the high mountains where they will spend most of the final part of the race. Their first battle will take place on the climb to Madonna di Campiglio on a day when the Italians will remember the late Marco Pantani who took a memorable stage win there in 2009 before being thrown out of the race due to a high haematocrit level.

The stage is 165km long and brings the riders from Marostica to the top of the Madonna di Campiglio climb and is a high mountain stage with a summit finish. The route initially passes through Valdastico, clears the La Fricca KOM climb (category 2, 11.3km, 5.1%, max. 10%) – a gradual climb with a gradient of around 6% in the first part before it levels out near the summit – and then runs down the long descent leading to Trento, where it takes in the first kilometres of the Monte Bondone climb where Mikel Landa won a stage at last year’s Giro del Trentino. From here, the route then heads towards Sarche, Terme di Comano and Tione di Trento. With 40 km remaining, the bunch will be confronted with the very challenging Passo Daone climb (category 1, 9.2%, max. 14%) that features an average gradient above 9%, and peaks reaching as high as 14% in the central sector and leaves almost no room for recovery as the gradient barely drops below the 9%. This is followed by a difficult descent, on a narrow mountain road, with some hairpin bends, and generally steep slopes up to Spiazzo. The route starts to rise again, first with a deceptive false-flat drag up to Pinzolo, then with an average 6% up to the last 3 km, after crossing the urban area of Madonna di Campiglio.

Starting in Carisolo, the final climb has a length of 15.5 km and an average gradient of 5.9%, with steady gradients of around 6.5% up to Madonna di Campiglio. The route runs across the urban area of the town (with a short setts-paved stretch) where it gets significantly easier with a 3km section of just 2.8%; the highest slopes (12%) are found outside the town. The last 2 km run at a 7% gradient on a well-paved asphalt road (with a 5.5 m width at the finish), with a short easier section from the 1.5km to 1.0km to go mark. There are two hairpin bends inside the final kilometre, with the final one coming with 500m to go from where the road bends very slightly to the right.

This is a big day for the GC and mainly climbers will be eager to take back some time already one day after the final time trial. However, the final climb is pretty easy and the difference will probably have to be made before the riders get to the easy section with 6km to go. This means that it is unlikely to do some major damage and is one of the reasons that Alberto Contador has vented his frustration over the lack of difficulty of the finishing climbs in this race. Depending on the situation after the time trial, the Spaniard may be in need to take back some time from Porte and it would be no surprise to see him use his strong team to make the race hard on the Passo Daone which is one of the hardest climbs of the race. With the final climb being pretty easy, however, there is a chance that the GC riders will allow a breakaway to take the stage win.

The climb has only been used as a stage finish once in the past: in 1999 when Pantani took that memorable win by distancing his main rivals by 1.07.

Rest day, Monday May 25

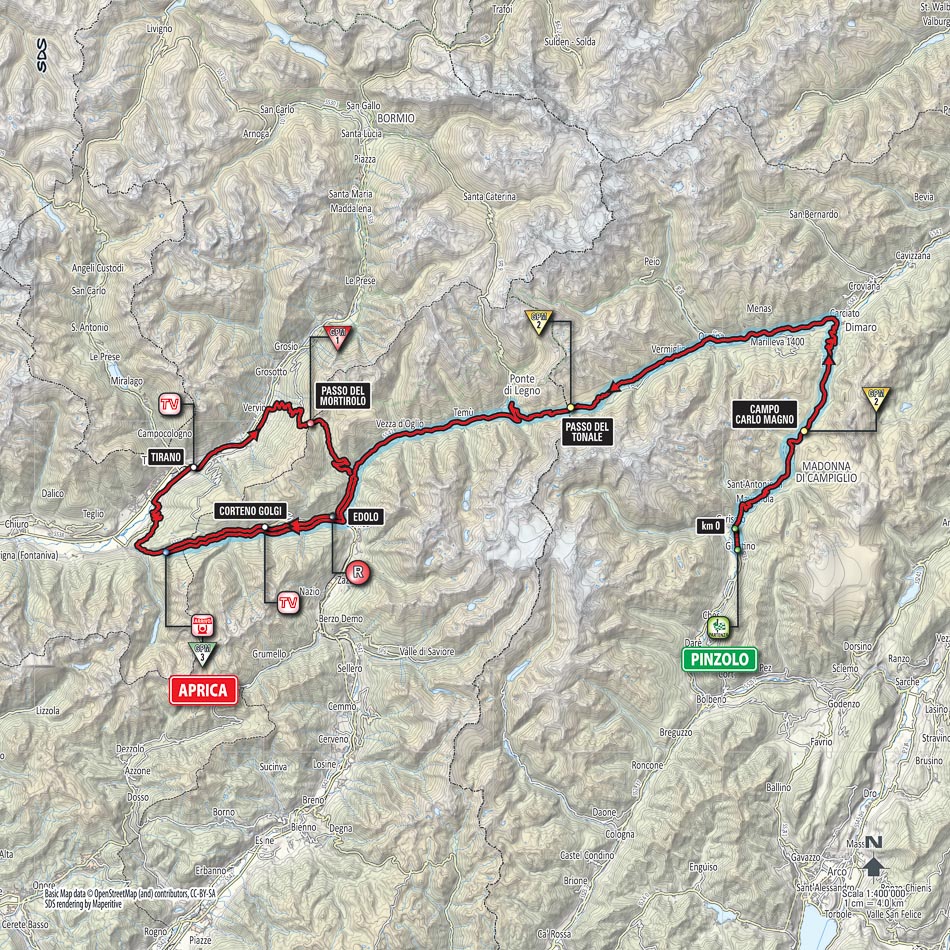

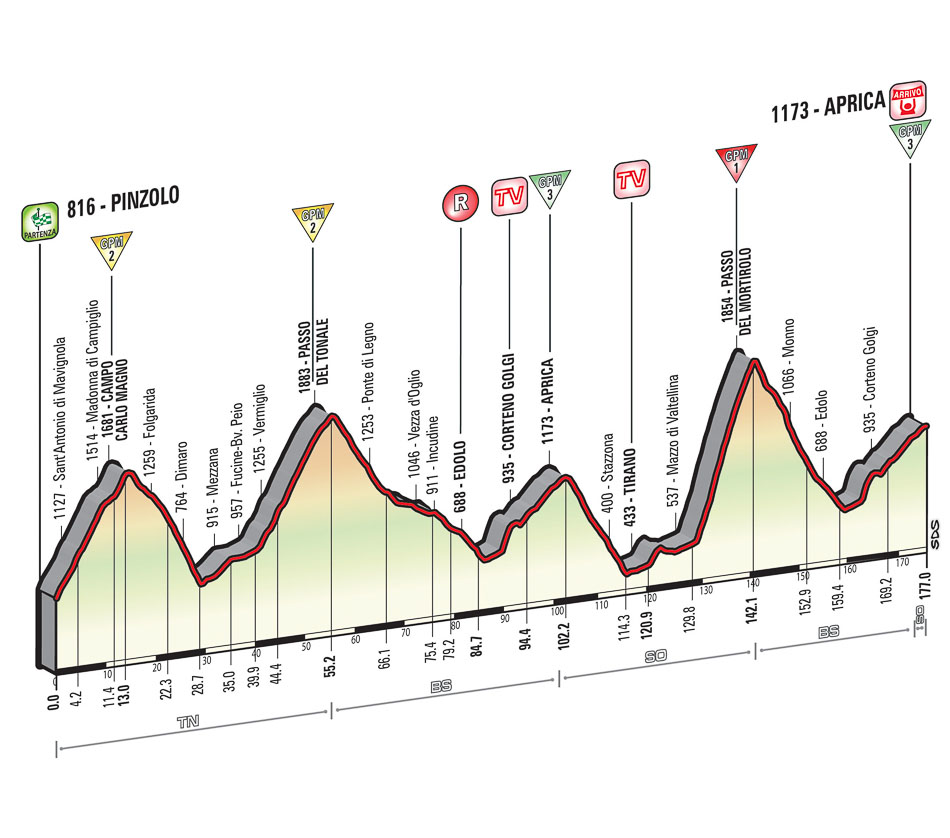

Stage 16, Tuesday May 26: Pinzolo – Aprica, 174km (*****)

One day after a rest day, many riders are a bit nervous about how their legs will react and so there wukk ve a very tense atmosphere when they gather in Pinzolo for the start of stage 16. For the second year in a row, the organizers have made stage 16 one day after the second rest day the hardest of the entire race. After a two-year absence, the legendary Mortirolo will be back but like in the previous stage, it is the penultimate ascent that is the hardest while the climb to the finish is a pretty easy affair.

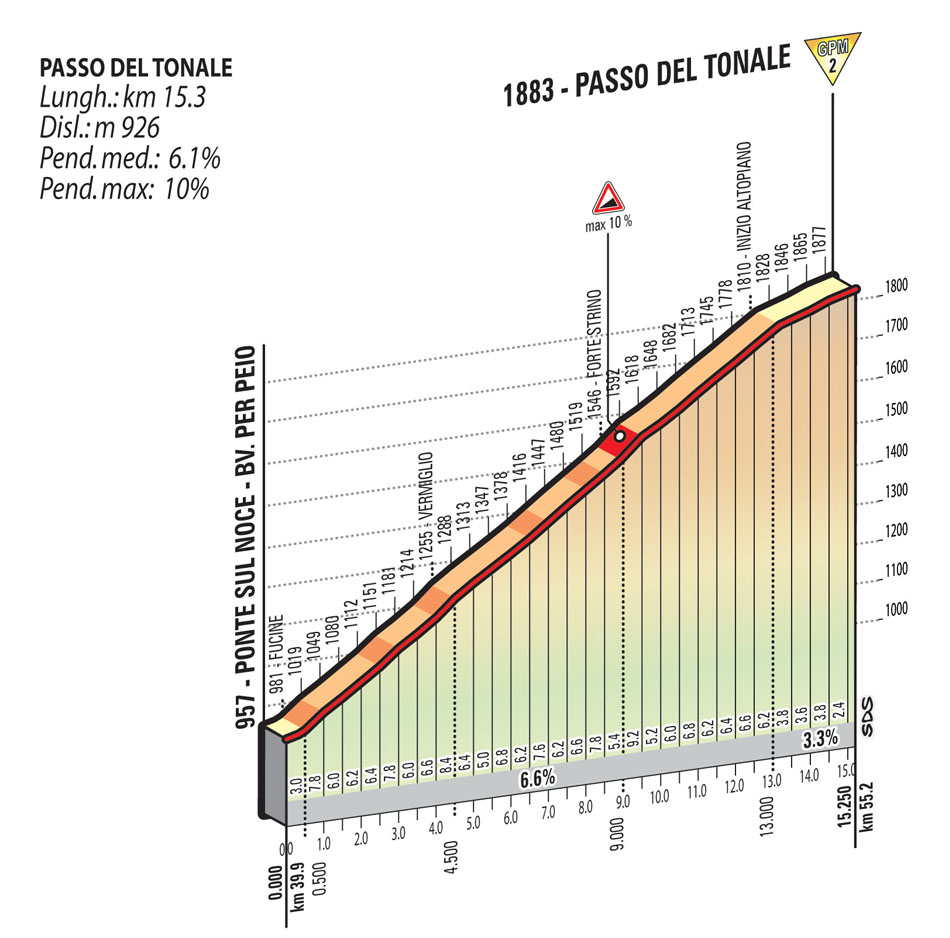

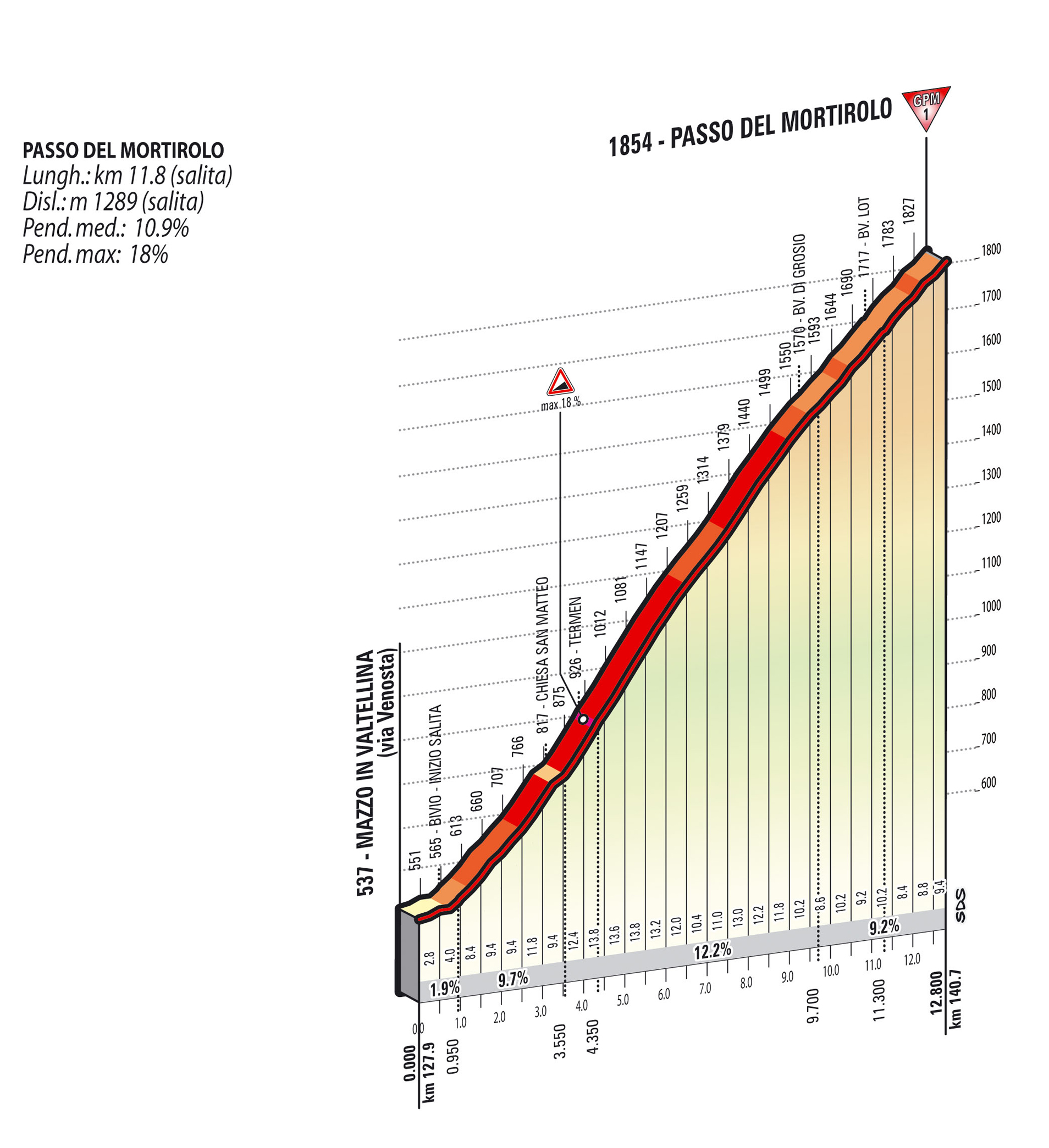

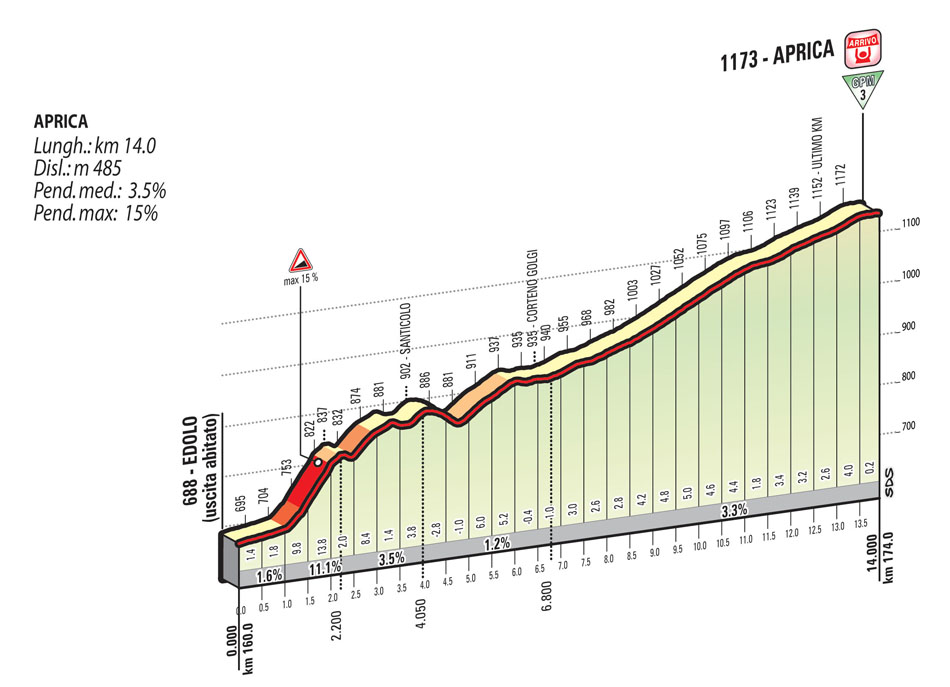

The stage brings the riders over 174km from Pinzolo to Aprica and is a high mountain stage with as many as 5 KOM climbs and a total difference in altitude of 4,500 m. The route starts uphill in Pinzolo, clears the Campo Carlo Magno climb (category 2, 13.0km, 6.7%, max. 12%, this is largely the same ascent as the previous stage), takes a fast-running descent into Dimaro and goes up again, towards Passo del Tonale (category 2, 15.3km, 6.1%, max. 10%, very regular before it levels out near the top) where Johann Tscopp won a stage in 2010. The stage course drops down into Ponte di Legno and Edolo, then takes in the first climb towards Aprica (category 3, 14.0km, 3.5%, max. 15%), through the village of Santicolo (with gradients of roughly 15% in the first stretch). After rolling past Corteno Golgi, the route takes the ss. 39 and heads for the first passage on the finish line. The following descent is initially wide and fast, and turns narrower and more technical all the way up to Stazzona. The route levels out briefly while running through Tirano (the only flat sector of the stage), then it tackles the Mortirolo climb along the traditional Mazzo di Valtellina slope (category 1, 11.9km, 10.9%, max. 18%, with a 12.2% gradient along the 6 kilometres of the central sector that always has two-digit gradients, and peaks of 18%). This is followed by a technical descent (on narrowed roadway in the first part), leading to Monno and then to Edolo, where the route will cover once again the 14 km leading to Aprica.

The final 14km runs entirely uphill, with remarkable gradients between Edolo and Santicolo (max. 15%), but flattens out gradually while approaching the finish, dropping to 5% with 5 km to go, and to less than 2% over the last 500 m. The finish line lies on a 7.5-m wide asphalt road, running gently uphill. There are no major technical challenges as it is just a long, slightly winding road.

There is no doubt that Mortirolo is the hardest climbs of the entire race and its brutally steep slopes usually split the peloton to pieces. However, the summit is located with 33.3km to go and this gives plenty of room for a regrouping to take place. The final climb to Aprica is more of a slightly rising road than a real climb and it is better suited to a chasing group than a strong climber who has dropped the rest on the Mortirolo. However, the finale is a well-known one and history shows that it is possible to take a solo win in this stage but it has also been won from a small sprint from a group of the strongest climbers in the race. If one fails to make it to the top of the Mortirolo with the best, however, this can be a very costly day where big time gaps can be created. Hence, it is one of the biggest chances for the climbers and they will all love to win a stage that includes the Mortirolo. Tinkoff-Saxo are likely to make things hard so the GC riders are likely to decide a stage but on a day with constant climbing and an uphill start, a breakaway always has a chance.

Aprica has hosted a stage finish 8 times in the past, most recently in 2010 when Michele Scarponi, Ivan Basso and Vincenzo Nibali distanced their rivals on the Mortirolo before Scarponi sprinted to the stage win. In 2006, Ivan Basso crested the summit of the Mortirolo alongside Gilberto Simon before distancing his companion on the final climb to Aprica. In 1999, Robert Heras beat Simoni and Ivan Gotti in a 3-rider sprint on the day when race leader Marco Pantani had been taken out of the race due to an elevated hematocrit level. Mortirolo last featured on the course in 2012 when the riders tackled the Stelvio climb in the finale and here it was Thomas De Gendt who rode away to a solo victory and almost took the overall win in the process.

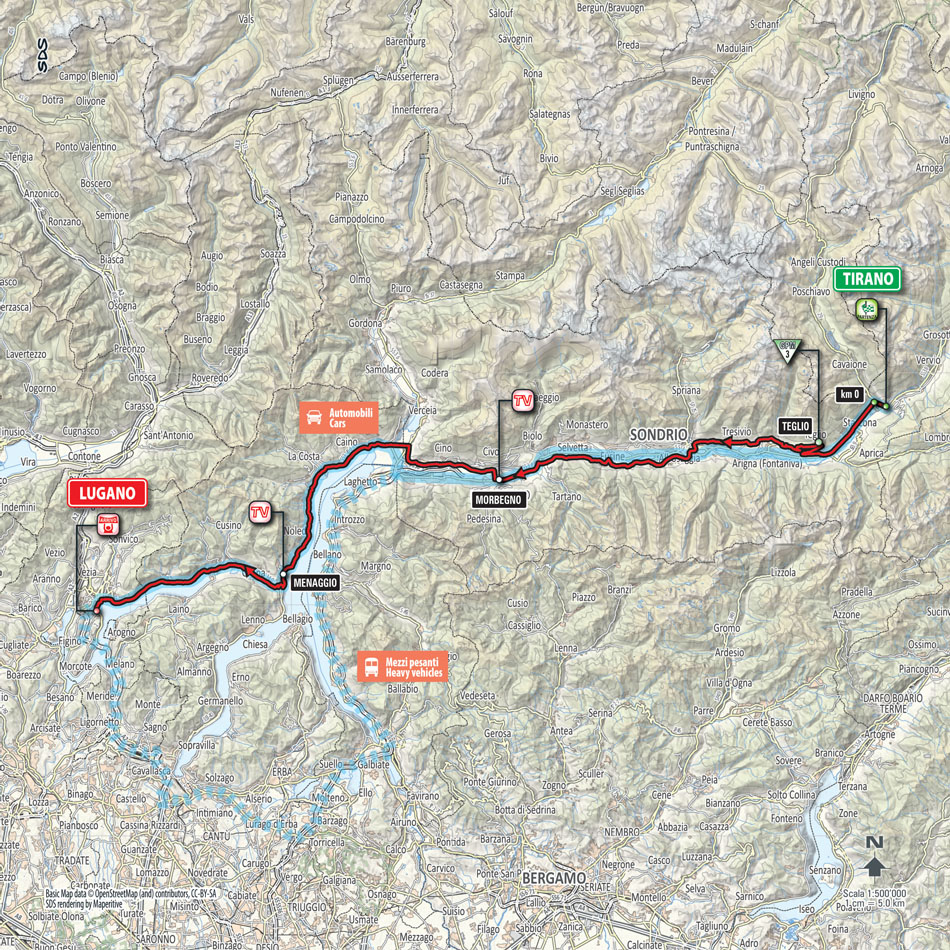

Stage 17, Wednesday May 27: Tirano – Lugano, 134km (*)

A few years ago, the final week of the Giro d’Italia included no sprint stages and gave the sprinters very little incentive to get through the massive amount of climbing in the final part. This year the third week is again loaded with big mountain stages but the organizers have followed the recent trend of including a few opportunities for the fast men and allowing the GC riders to get a small breater.

This year the final week has two chances for the sprinters and the first of those comes on stage 17. The course brings the riders over just 134km from Tirano to Lugano for a finish in Switzerland just across the border. The stage will partly allow the riders to regain their strength. It is most suitable to sprinters, but it is not completely flat. The only KOM climb of the stage is just after the start, with the Teglio ascent (category 3, 7.4km, 6.5%, max. 10%). The Valtellina scenic route runs across Poggiridenti and leads to Sondrio. Here, the stage course enters the Adda River valley, and runs along it until it reaches the mouth of Lake Como. The roadway narrows all along the lakefront road leading to the short Croce di Menaggio climb. The following stretch of road leading to Lake Como has a few tunnels along the route. The last 3 km run across the urban area of Lugano. The riders will have to watch out for a number of obstacles, such as roundabouts, speed bumps and traffic dividers, while crossing urban areas.

In the finale, there is a small climb which summits with a round 4km to go. The last kilometres run initially downhill (with two close hairpin bends 3 km before the finish), then along the shores of Lake Lugano for the final 2 flat kilometres, on well-paved roads. There are sharp turns with 2.5km and 1km to go. The route features one last bend 750 m from the finish, on 7-m wide asphalt road.

With André Greipel being a possible exception, most of the sprinters plan to finish the race as they have no intention of doing the Tour de France. This means that there should be plenty of interest in keeping it together for a bunch sprint. At this point in a grand tour, however, there is always a chance that a breakaway will make it as the domestique resources are limited and everybody is tired. As this stage has a very tough first part, the break may simply be too strong to catch and the slightly undulating finale may also favour a breakaway. However, the most likely scenario is that the sprinters will fight for the win in Lugano and if that is the case, they have to be well-positioned in the tricky finale where the many turns and winding road will make team support very important.

Lugano has hosted a stage finish twice in the past, most recently in 1997 when Serguei Honchar won the stage.

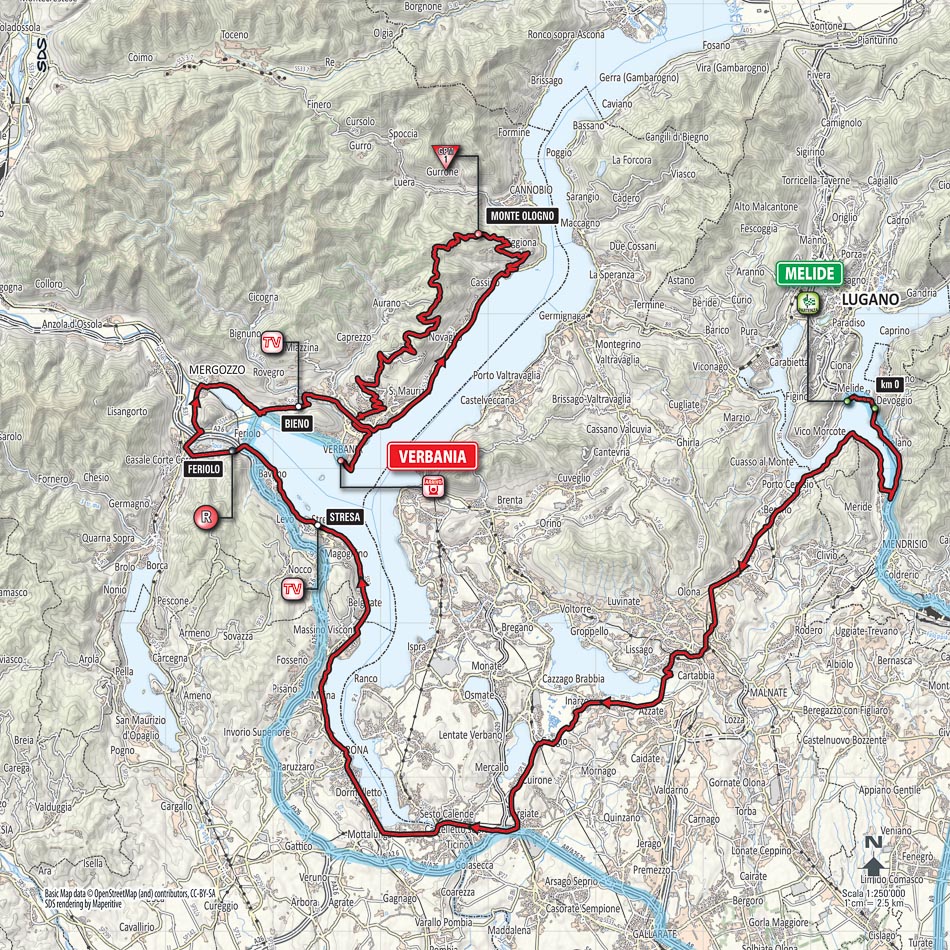

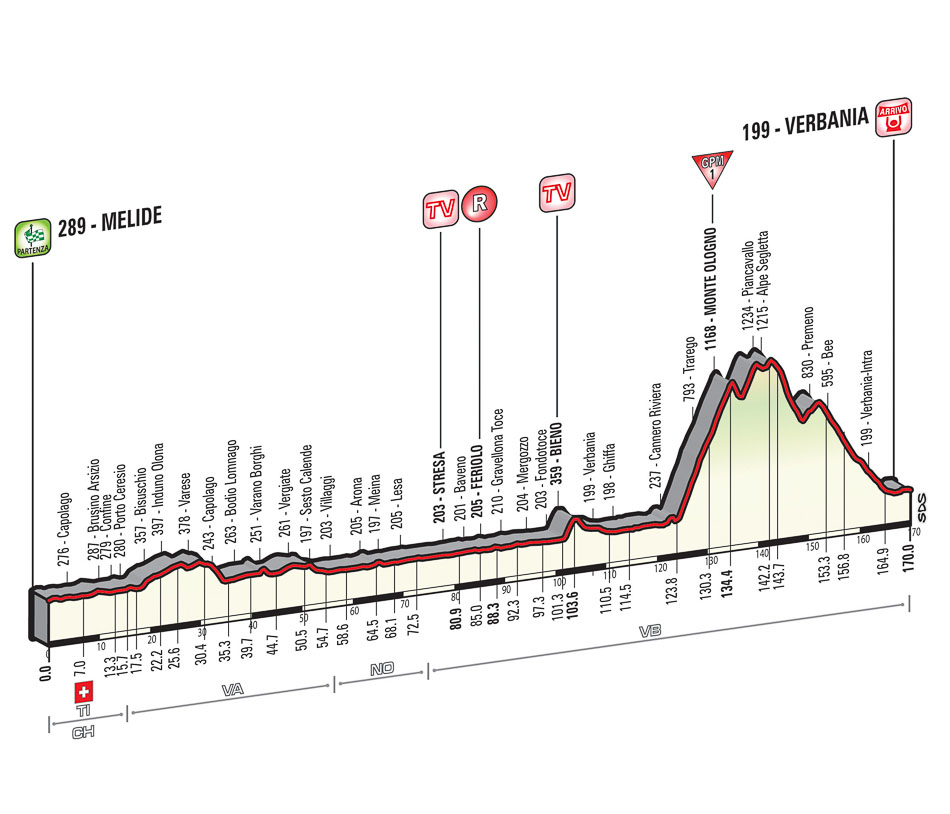

Stage 18, Thursday May 28: Melide – Verbania, 170km (***)

After a day in the flatlands, it is back into the mountains for stage 18 which offers a very rough finale and one of the hardest climbs of the race. However, the stage also features a downhill run to the finish and this means that it may not make a very big difference between the best climbers in the race. Instead, many stage hunters have red-circled this stage as maybe their biggest opportunity in the final week.

The 170km stage brings the riders from Melide to Verbania and is clearly divided into two parts. The first, flat 125 km run from Melide, along the shores of Lake Lugano, lead back to Italy and roll across Varese and Sesto, to reach Lake Maggiore. The route skirts around the lake through Arona and Stresa, reaching Mergozzo and Verbania (first time), brushing very close by the finish line. The riders have to watch out for a number of obstacles, such as roundabouts, speed bumps and traffic dividers, while crossing urban areas. The route rolls past Verbania and gets to the Monte Ologno ascent that features steep gradients (category 1, 10.4km, 9.0%, max. 13%). It is a very regular climb that leaves virtually no room for recovery and has a pretty constant gradient above 8%. The first part of the descent is curvy and technical, but with low gradients. As the stage course reaches Alpe Segletta, the second part is wider and easier. The descent ends 5 km from the finish and includes a few small climbs along the way.

The last 17 km run along a wide, well-paved downhill road leading from Premeno to Verbania (a former railway with slopes of approx. 5%), up to 5 km from the finish in the built-up area of Verbania (Intra). The route rolls past a few roundabouts and traffic dividers, and eventually reaches the waterfront. The last 3.5 km are quite uncomplicated as the riders will just follow a long, slightly winding road, with a sharp turn just after the flamme rouge. The finish line lies on a 200-m long straight, on 6.5-m wide asphalt road, after the riders have tackled a very slight bend.

This stage has breakaway written all over it as this kind of downhill finish means that the stage has no obvious favourite. Even though the descent includes a few technical sections, it will be hard for a single rider to keep the chasers at bay and with two big mountain stages to come, the GC riders are likely to save their teams for later. This means that the early escapees are likely to decide the stage and it could be a very interesting affair as the easy first part means that the break may not have a lot of strong climbers. The final climb is so tough that it can be used to create some differences and we may see some attacks from the GC riders. A group of the best climbers are likely to reach the finish together and so this is not a day to win the race but on a bad day, everything can be lost on this hard ascent.

Verbania has hosted a stage finish twice, most recently in 1992 when Franco Chcioccioli won the stage.

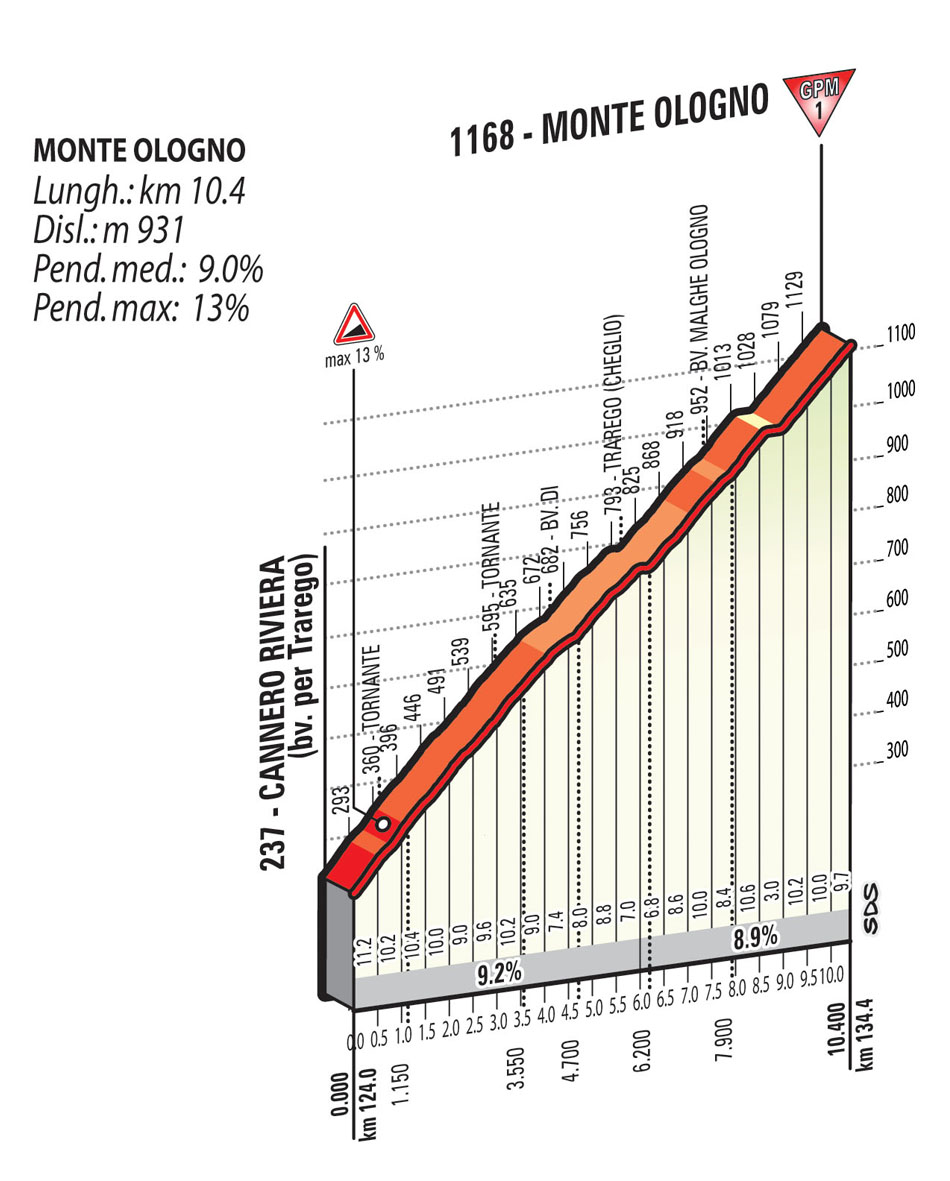

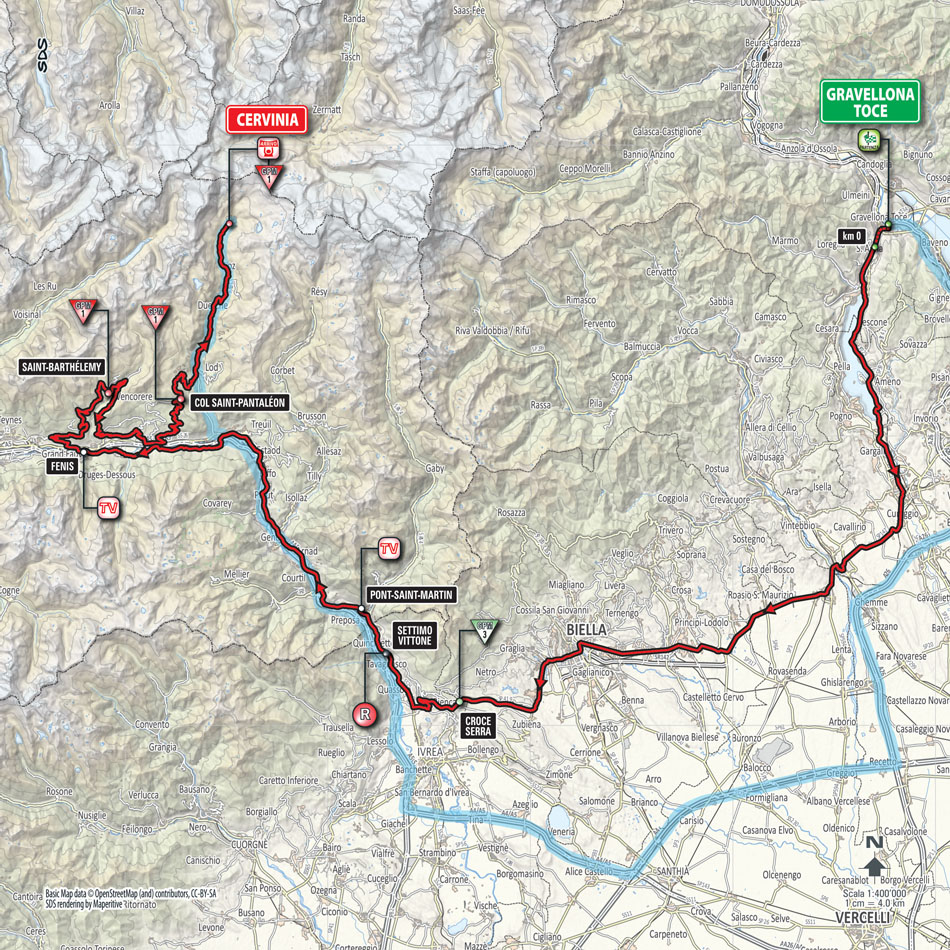

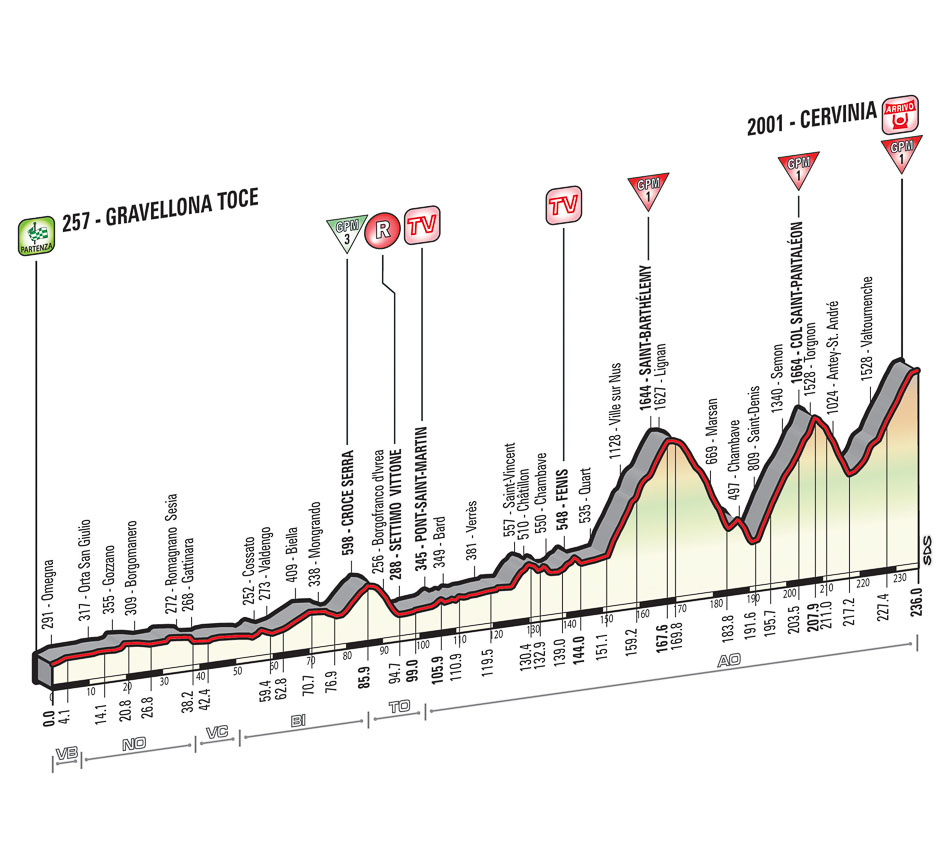

Stage 19, Friday May 29: Gravellona Toce – Cervinia, 236km (*****)

As it was the case last year, the race ends with three consecutive stages in the mountains before the final flat stage. After the moderately hard opener, the triptych continues with a brutally tough stage in which the combination of hard climbing, three weeks of tough racing and a long distance of 236km will take its toll. This is the penultimate chance for the GC riders to make a difference and as the finishing climb in stage 20 is pretty easy, it may even be their best opportunity.

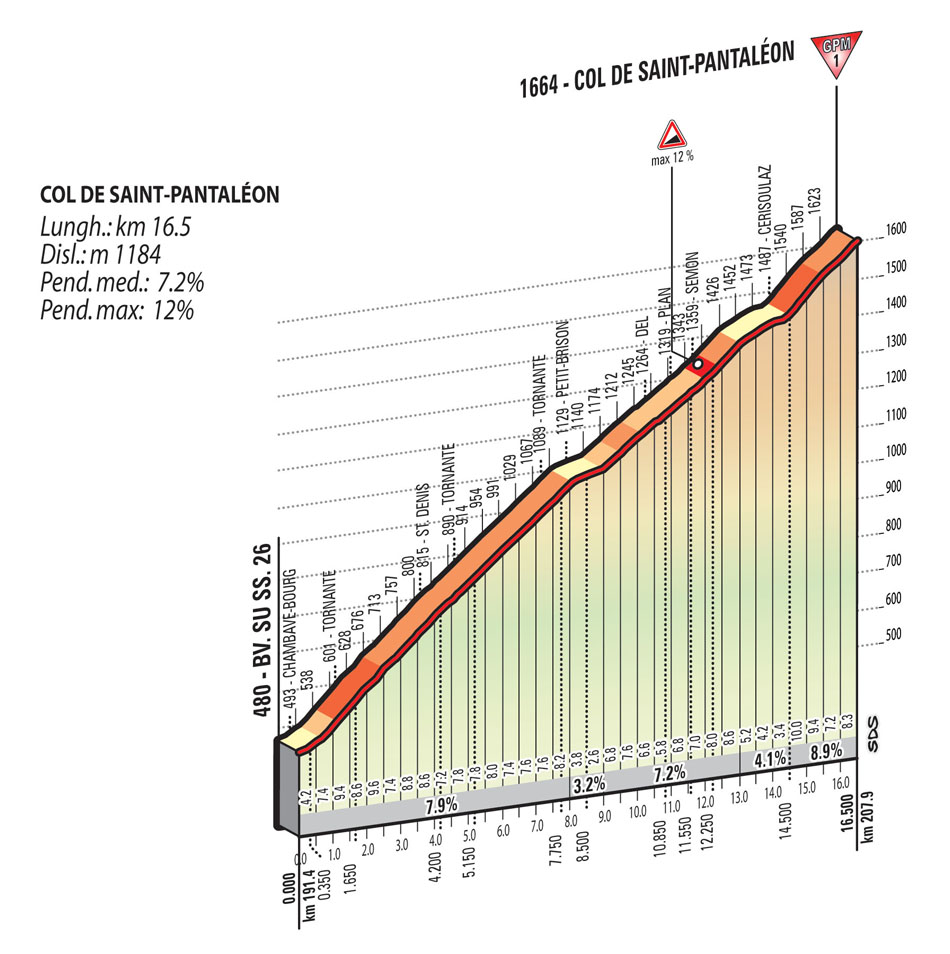

The course brings the riders over a massive 236km from Gravllona Toce to a summit finish in Cervinia. This queen stage through the Alps features a total difference in altitude of approx. 4,800 m, that is covered almost entirely over the last 100 km, with 3 subsequent climbs, measuring up to 20 km each. The route winds its long journey around the Alpine foothills through the districts of Borgomanero and Biella with the Croce Serra climb (category 3, 6.9km, 3.8%, max. 9%), and then it enters the Aosta Valley, where the last 150 km of the stage will take place. The stage course tackles the St. Barthélemy ascent (category 1, 16.5km, 6.7%, max. 13%, pretty irregular with a steep start and then several easier sections along the way), St. Pantaléon (category 1, 16.5km, 7.2%, max. 12%, a tougher climb with 3 regular 7-8% sections divided by two easy parts) and, eventually, it ramps up the Cervinia climb (category 1, 19.2km, 5.0%, max. 12%).

The final climb is not very hard. The first four kilometres average 2.5% and then the riders reach 2km with a gradient of 7.2%. Then it’s another almost completely flat section before the riders get to the steepest part, a 1.5km stretch with a gradient of 7.8. The following 6km are pretty regular at 5-7%. The last kilometres run entirely uphill. The route rises with the steepest slope just before, and while crossing, the town of Valtournenche. The climb starts to level out gently 3 km before the finish. With less than 2,000 m remaining to go, the average gradient is 1.4%. The 450-m long home straight, on 7-m wide asphalt road, has a 4% gradient. Over the last 6 km, the stage course features two well-lighted tunnels. There are no major technical challenges in the finale as the final hairpin bends comes with 3km to go and then the road is only slightly winding in the final part.

With three big climbs, this is evidently a tough mountain stage but none of the climbs are very steep. The final ascent is even the easiest of the trio and it does not include any very steep sections. In fact the final 2km are almost flat and so it may not create very big time differences. To make this stage decisive, it needs to be made hard by one of the stronger teams and much will depend on the situation on GC. If he is still in need of time, Alberto Contador may use his strong team on the two early climbs and if he also needs the time bonus, he will bring the early escapees back. Otherwise, this seems to be a stage for a breakaway as it is not very prestigious, is followed by another tough mountain stage and is so long that it requires a big effort to control.

The Cervinia climb has been used as the final ascent thrice, most recently in 2012. Here Andrey Amador, Jan Barta and Alessandro De Marchi made it to the finish in a breakaway and it was the Costa Rican who won the three-rider sprint. Ryder Hesjedal attacked out of the group of favourites to earn 26 seconds but the final climb didn’t do much damage as only very small splits appeared in the 15-rider group of favourites.

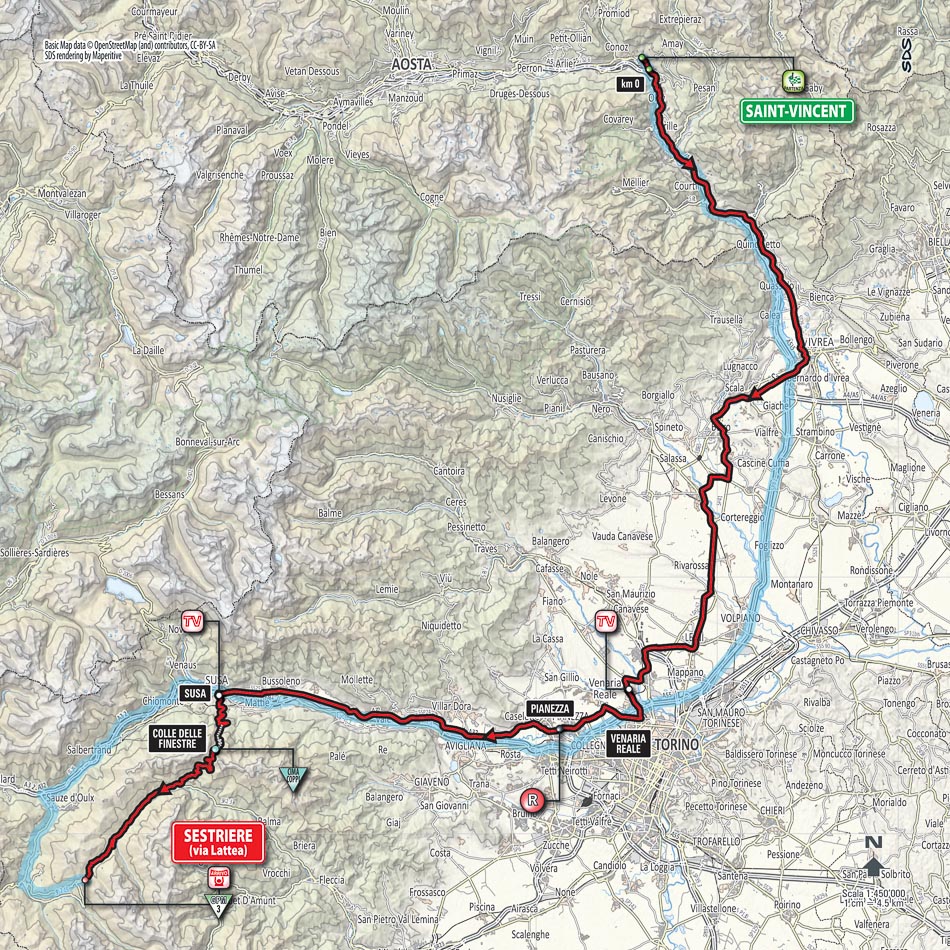

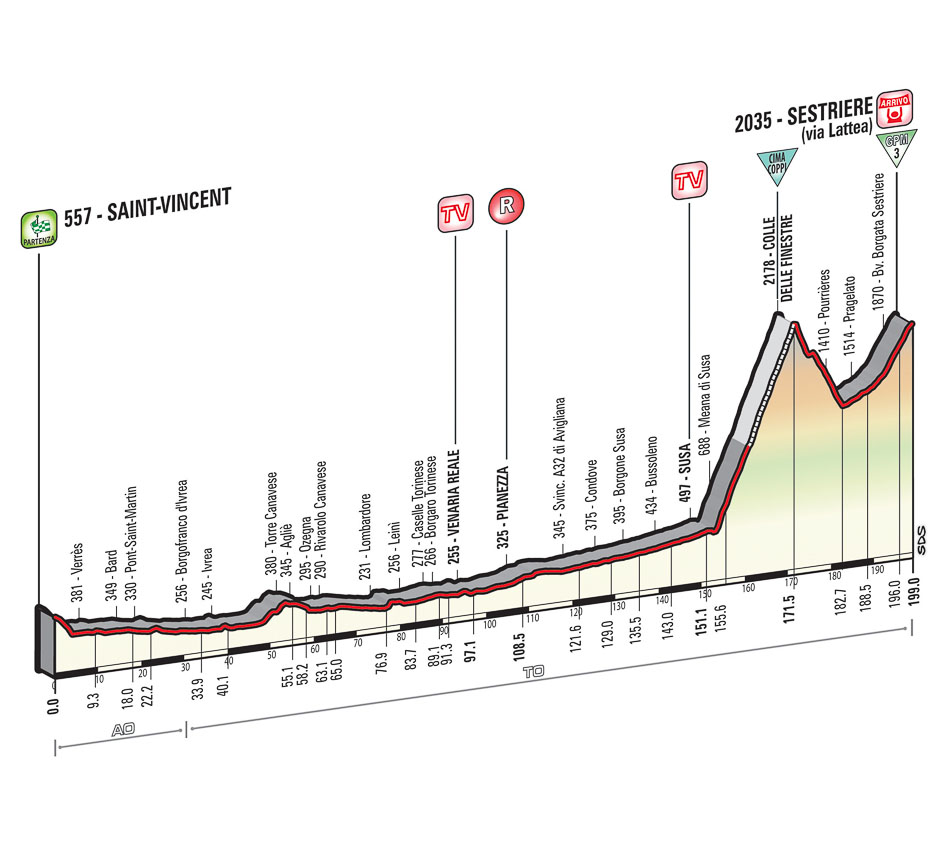

Stage 20, Saturday May 30: Saint-Vincent – Sestriere, 199km (****)

In recent years, the organizers have always included a big mountain stage on the penultimate day of the race and they have always made sure that one of the most spectacular climbs feature on the course. In 2012 the riders tackled Mortirolo and Stelvio on the penultimate day, in 2013 Tre Cime di Lavaredo featured one day before the finish and last year Monte Zoncolan was the decisive climb. In 2011, the famous gravel roads of the Colle delle Finestre provided a huge spectacle on stage 20 and it will again be that tough climb that decides the race.

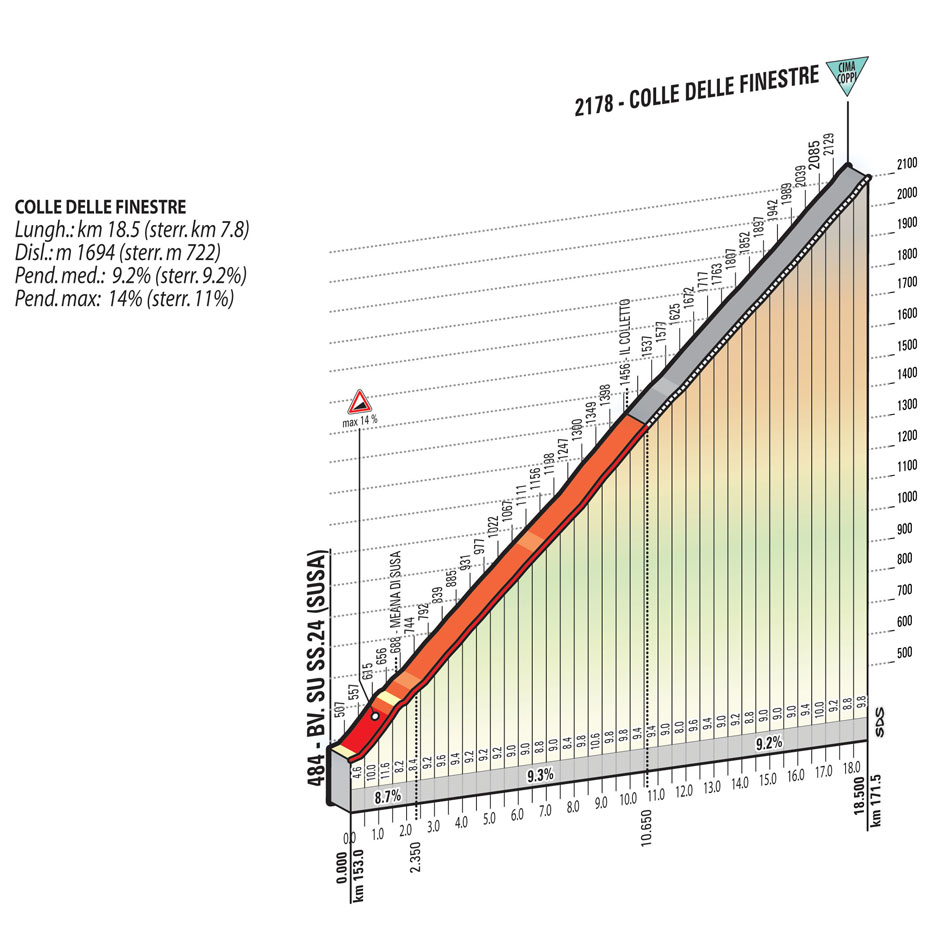

The 199km stage form Saint-Vincent to Sestriere is virtually identical to the one that was used three years ago. This high mountain stage features the last summit finish of this year’s Giro. The first 150km run across the whole upper Po Valley, and serve as warm up towards the Colle delle Finestre climb. The route rolls through the Canavese area via Ivrea and Rivarolo Canavese, it rolls past Venaria Reale and reaches the Susa Valley. The Colle delle Finestre climb (category 1, 18.5km, 9.2%, max. 14%) features a steady 9.2% gradient, from foot to summit (with just a short spurt in Meana di Susa with a max. 14% slope). The road is paved over the first 9 km, while the remaining 9 km run on dirt road, up to the summit. The first part of the ascent features as many as 29 hairpin turns in less than 4 km (totalling 45 hairpins up to the summit). It is a hugely regular climb with a very constant gradient. In the first part (up to Pian dell’Alpe), the descent is technical, narrow and not protected.

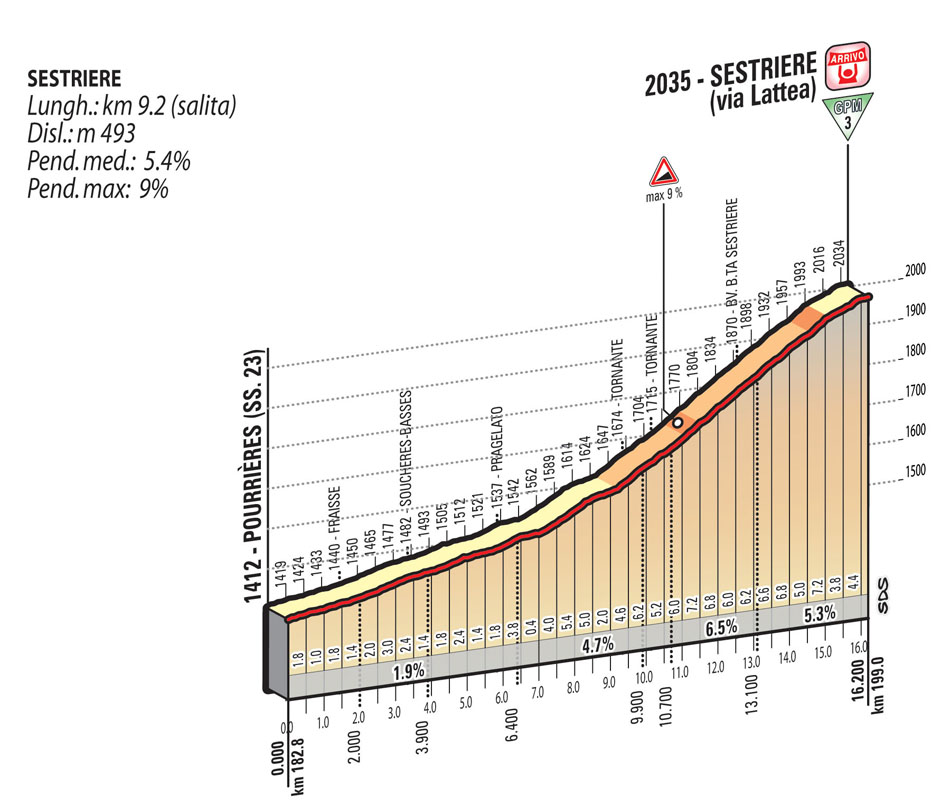

As the stage course goes back to ss. 23, the climb ramps up again, with pretty easy slopes, up to the finish in Sestriere (category 3, 9.2km, 5.4%, max. 9%). The first 4km have a constant 4.5% gradient before the riders get to a short steeper 6-7% section that ends one kilometre from the finish. From there, the gradient is only around 3%. The last kilometres run along the ss. 23, with wide and well-paved roadway, with just a small roundabout 500 m from the finish. The 400-m long home straight is on 6.5-m wide asphalt road.

Everybody knows that to expect from this stage as the finale is identical to the ones that were used in 2005 and 2011 and it provides the GC riders with one final chance to deal their rivals a blow. The Colle delle Finestre is a beast whose steep, regular gradients can do a lot of damage but the final climb to Sestriere is very easy and unable to make much of a difference. The decisive attacks have to be made on the Finestre but it will be hard for a lone rider to keep chasers at bay on the gradual uphill to Sestriere that suits a group more than a lone rider. Furthermore, these late spectacular stages have often failed to live up to expectations and have rarely created too big differences at a point when everybody is very tired. If Alberto Contador has already stamped his authority on the race, he will be looking to the Tour de France and will hope to get as easy through this stage as possible and a breakaway definitely has a chance like in 2011. On the other hand, everybody would love to win a stage that includes the Finestre and as there is no reason to save the domestiques, the most likely scenario is that the GC riders will fight for the win.

Sestriere has hosted a stage finish 6 times in the past, most recently in 2011 when a very strong Vasil Kiryienka completed a successful escape while Jose Rujano and Joaquim Rodriguez managed to gain some time over their rivals on the final climb to Sestriere. In 2006, Jose Rujano took a memorable solo win in his breakthrough race as held off Gilberto Simoni by 26 seconds while Paolo Savoldelli limited his losses to defend the overall lead. In 2000, Jan Hruska won a mountain time trial from Briancon on the penultimate day while Stefano Garzelli finished third to seal his overall win in the race.

Stage 21, Sunday May 31: Torino – Milano, 178km (*)

Unlike the Tour and the Vuelta which always finish in Paris and Madrid respectively (even though the Vuelta deviated from that pattern in 2014), the final destination of the Giro varies a bit. It is very often Milan that has hosted the final stage of the Italian grand tour but in 2009 the race finished in Rome and in 2010 Ivan Basso was declared winner in Verona. After finishes in Milan in both 2011 and 2012, the 2013 edition will finished in Brescia and for the first time since 2007 when Maximiliano Richeze sprinted to a win in Milan, the final stage was not a time trial as Mark Cavendish ended his impressive Giro campaign by taking another stage win. Last year the race finished in Trieste and again the organizers had decided to give the sprinters a chance to shine, with Luka Mezgec sprinting to the win.

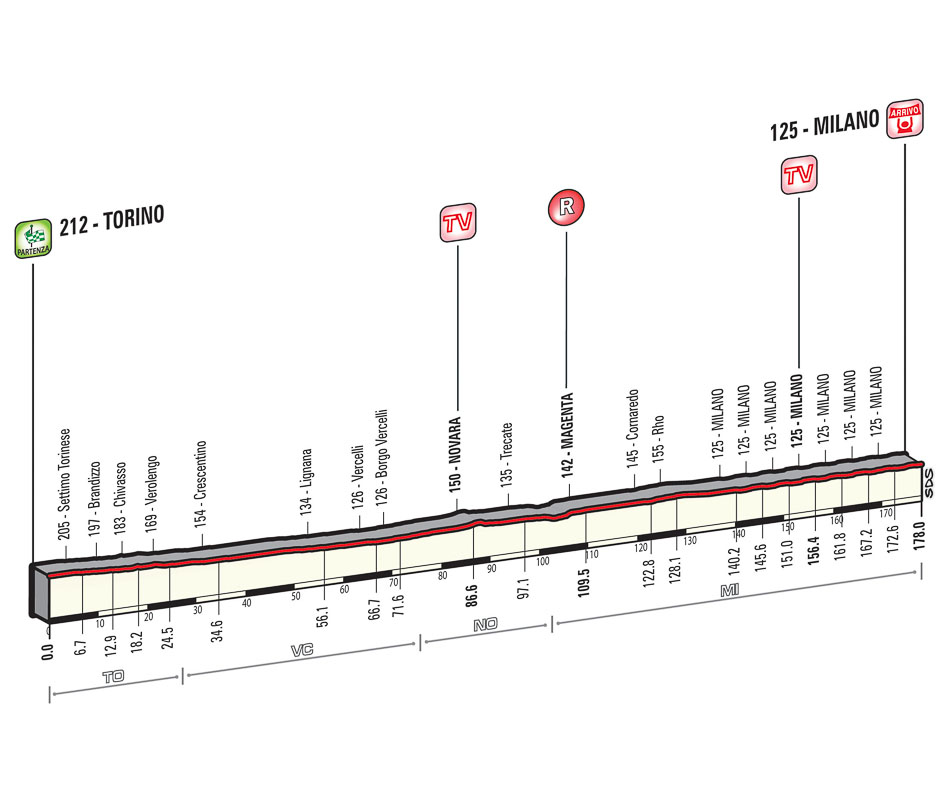

This year the race will return to Milan and again the organizers have decided to skip the time trial in favour of a stage for the sprinters. They have received some criticism for making these often largely processional stages pretty long but they have still not decided to change their script. This year the desire to link the two major cities of Turin and Milan and include a few laps of a finishing circuit means that the riders will have to cover no less than 178km on the final day before the sprinters can stretch their legs.

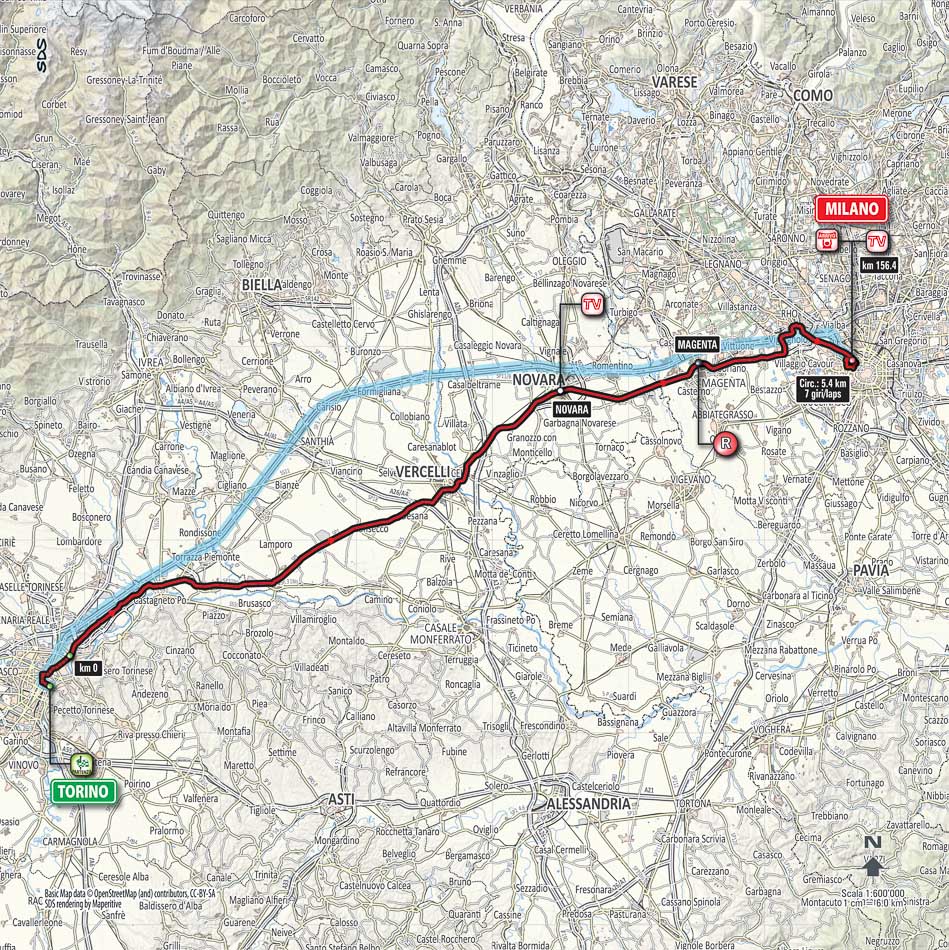

Starting from Turin, the route rolls through the Po Valley along entirely flat roads, and reaches Milano. The stage course covers wide and mainly straight roads, with just a few city-centre crossings, with roundabouts, speed bumps and traffic islands being the main, “typical” obstacles. The route arrives in Milano through Pero and the Expo site, and it enters the final 5.4-km circuit, to be covered 7 times, and finishing in Corso Sempione.

The final circuit (5,350 m) stretches along wide, well-paved avenues around the Vigorelli velodrome and the Fiera Milano City fairground. It features 8 bends and 4 half-bends, and it crosses a tram-line twice (vertically). That makes it a pretty technical affair and the penultimate kilometre is very challenging as it includes two sharp turns and a roundabout. The final right-hand turn comes just after the flamme rouge. The home straight is 1 km long, on 8.5-m wide asphalt road.

The stage will pan out as a usual final road stage of a grand tour, with a ceremonial first part in a relaxed mode and a very hectic finale. Due to the long distance, however, the riders will have to ride a bit faster for a bigger portion of the stage and they cannot wait for the finishing circuit to accelerate. We may even see attacks and a breakaway before we get to the circuit. In the end, the race will develop into a high-speed criterium where the sprint teams will not leave much room for the attackers on this kind of technical circuit. With the many technical challenges, it will be important to be well-positioned but with a long, wide finishing straight, it will be a high-speed affair for the pure sprinters with the highest top speed.

Milan has hosted a stage finish on 84 previous occasions, most recently in 2012 when Marco Pinotti won a time trial. In 2011, David Millar won the final time trial while Mark Cavendish won a bunch sprint in 2009 when the race unusually visited the city at the midpoint of the race. In 2008, Pinotti was again the fastest in a time trial while Alessandro Petacchi is the latest rider to have won a bunch sprint in Milan on the final day in 2007 (although he has later been disqualified due to a positive test for Salbutamol, meaning that Maximiliano Richeze is the official winner of the stage).

| Taylor WARREN 32 years | today |

| Dejan VIDAKOVIC 42 years | today |

| Alfredo GABINO 41 years | today |

| Fredy BUERGOS 38 years | today |

| Sang Hyup LEE 32 years | today |

© CyclingQuotes.com